A big spring boost for one of Denver Water’s most important bank accounts

One of Denver Water's most important bank accounts is Lake Powell, a reservoir some 600 miles away. And it’s expected to see bigger-than-average inflows this year after a strong snow season throughout the Colorado River Basin.

It’s good news not only for Denver Water, but for all of Colorado and the 40 million people who rely upon the Colorado River for their water supply. The upper basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico depend on Lake Powell to hold the water they are legally required to send downstream to the lower basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California.

“One big snow year doesn’t end the 19-year drought in the basin — but it helps, it’s welcome,” said Rick Marsicek, planning manager for Denver Water. “But we can’t rest. We’re focused relentlessly on how we adapt to what may very well be a drier Colorado River in the years to come.”

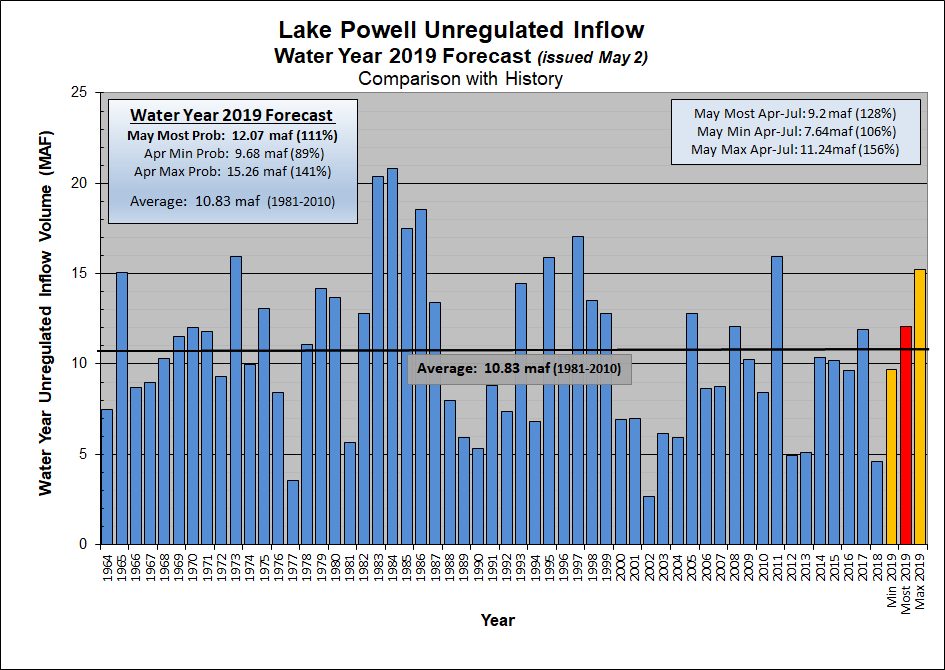

In its latest May 10 update, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projected just over 12 million acre-feet of water would flow into Lake Powell this year. That’s an enormous improvement over the 4.6 million acre-feet that flowed into the giant reservoir in 2018 and well above the 30-year average of 10.83 million acre-feet. The 30-year average covers the years 1981 through 2010.

This year's better-than-average injection of water is also a welcome shift from the below-average trend seen during the last 19 years.

Since 2000, inflows into Lake Powell have been above the 30-year average only four times. This year will be the fifth time — if predictions about this year's inflow hold true.

Years of low flows have exacerbated the “bathtub ring” effect, the ring of bare, lighter-colored rock visible above the reservoir's current water level. The width of the bathtub ring is a stark demonstration of how far water levels have fallen in Lake Powell. It's one of the most visually compelling symbols of long-term drought in the American Southwest.

Years of low flows have exacerbated the “bathtub ring” effect, the ring of bare, lighter-colored rock visible above the reservoir's current water level. The width of the bathtub ring is a stark demonstration of how far water levels have fallen in Lake Powell. It's one of the most visually compelling symbols of long-term drought in the American Southwest.

This long-running drought, what academics are beginning to call “aridification,” also brought together all seven states plus Native American tribes in the basin to develop “drought contingency plans.” The plans came together quickly over the last year and congressional legislation approving the plans was signed by President Donald Trump last month.

But the hard work is only beginning.

For Denver Water, Colorado and the other upper basin states, the agreement on a drought contingency plan is important, but really only amounts to a “plan to plan.” This is the first step in building agreement on how to ensure enough water gets to Lake Powell to prevent a so-far unprecedented scenario when the upper basin states fall short of their legal obligation to the lower basin states.

Denver Water CEO/Manager Jim Lochhead has consistently argued for aggressive planning for future shortages in the Colorado River Basin. One big snowpack year is heartening news, but no reason to rest.

“One of the lessons we’ve learned is that things happen more quickly than we ever thought they could,” Lochhead said. “Climate uncertainties have amplified the challenge; witness the swing in snowpack from a dry 2018 to a bountiful 2019.”

“As water managers, you have to plan for the worst,” he said, “so we’re going to have to be adaptable and flexible as we go forward.”