A 'lost' reservoir and a hike into history

There are ghosts in the wilderness.

Snacking on a granola bar four and a half miles down the Goose Creek Trail in the Pike National Forest, I was staring up at one.

It was a project that seemed incomprehensible. It’s hard enough just to make the relentlessly up-and-down hike to the spot. The thought of a man-made lake and a dam about the size of Gross Reservoir in Boulder County, holding enough water for 100,000 homes, nestled in such a remote region, was jarring.

Of course, it’s only fair to say that many reservoirs of today, including those operated by Denver Water, probably seemed just as hard to fathom decades ago. And yet, determined engineers found a way to build them.

All these years later, Denver Water still owns a bunch of the land at the site of the never-built Lost Park reservoir in the Pike National Forest, though you’d never know it; there’s no signage and access is unfettered.

You can bounce around the bizarre granite towers and let your head spin at the idea of what they tried to do here well over a century ago.

This kind of place is one reason my wife, Sherry, and I enjoy backpacking in Colorado’s wealth of federally protected wilderness areas. You can find ghosts of history like this, sometimes lingering right off the trail.

The ghosts can take many forms. Maybe a lonely stone chimney, the sole remains of a long-ago cabin; a stretch of mining road reclaimed by waist-high conifer trees; scraps of rusty iron, once important to some frontier implement.

A long walk into yesterday

Here’s a story about one of my favorite ghosts. It lies a couple of hours southwest of Denver, within the 120,000 enchanting acres of a place called the Lost Creek Wilderness Area.

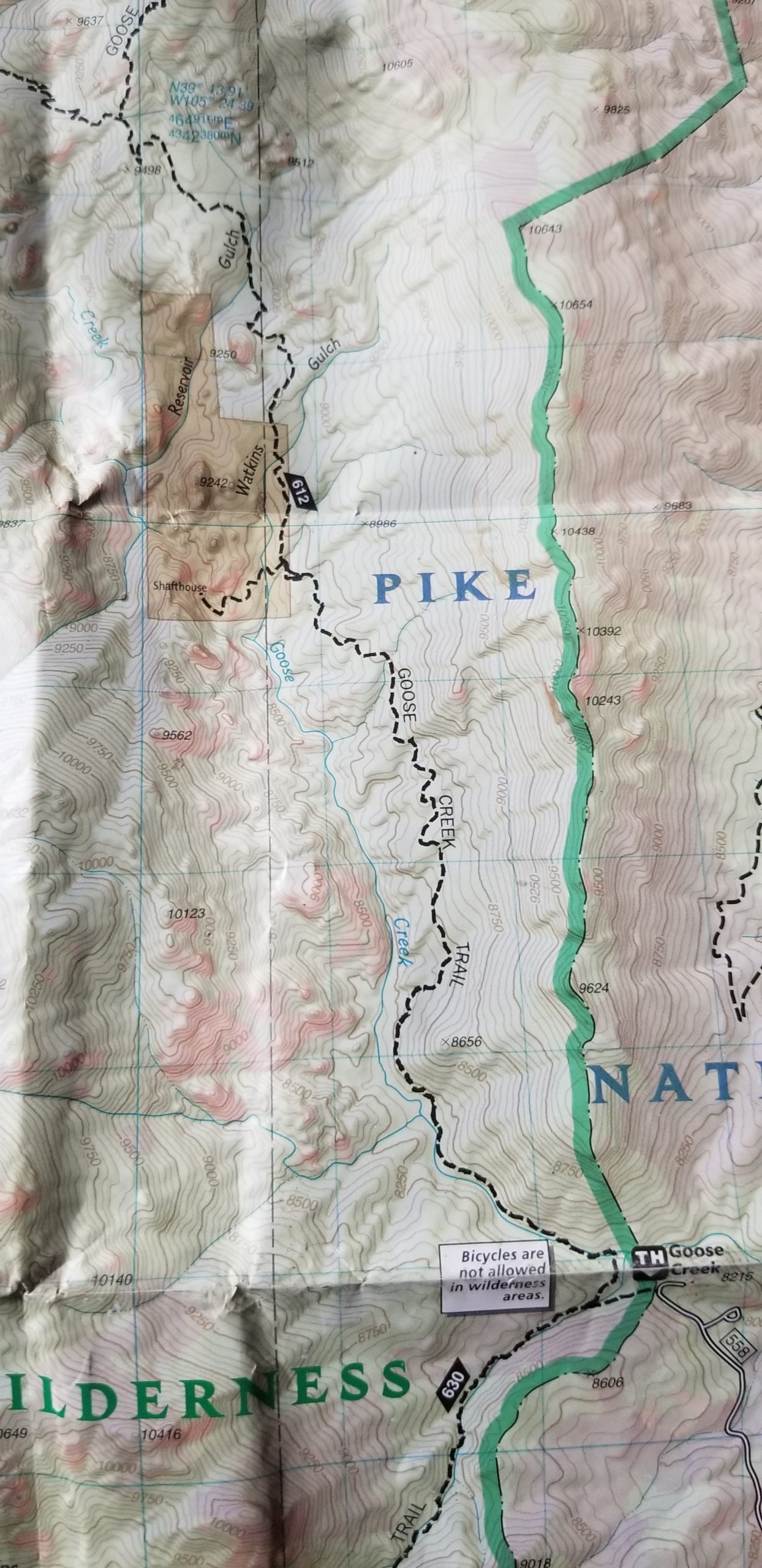

To be clear: it’s the driving that’s a couple hours, and that includes a bouncy, dusty 45 minutes on Forest Service Road 211. Once you park the car, you’ll have to walk another two or three hours. We’re solidly middle-aged, so we take the over on that one.

But if you like to time travel, the payoff is big.

About four miles down Goose Creek Trail you come to a surprising site: The robust skeletons of two big cabins, dating to the 1890s. The remains of others sit nearby.

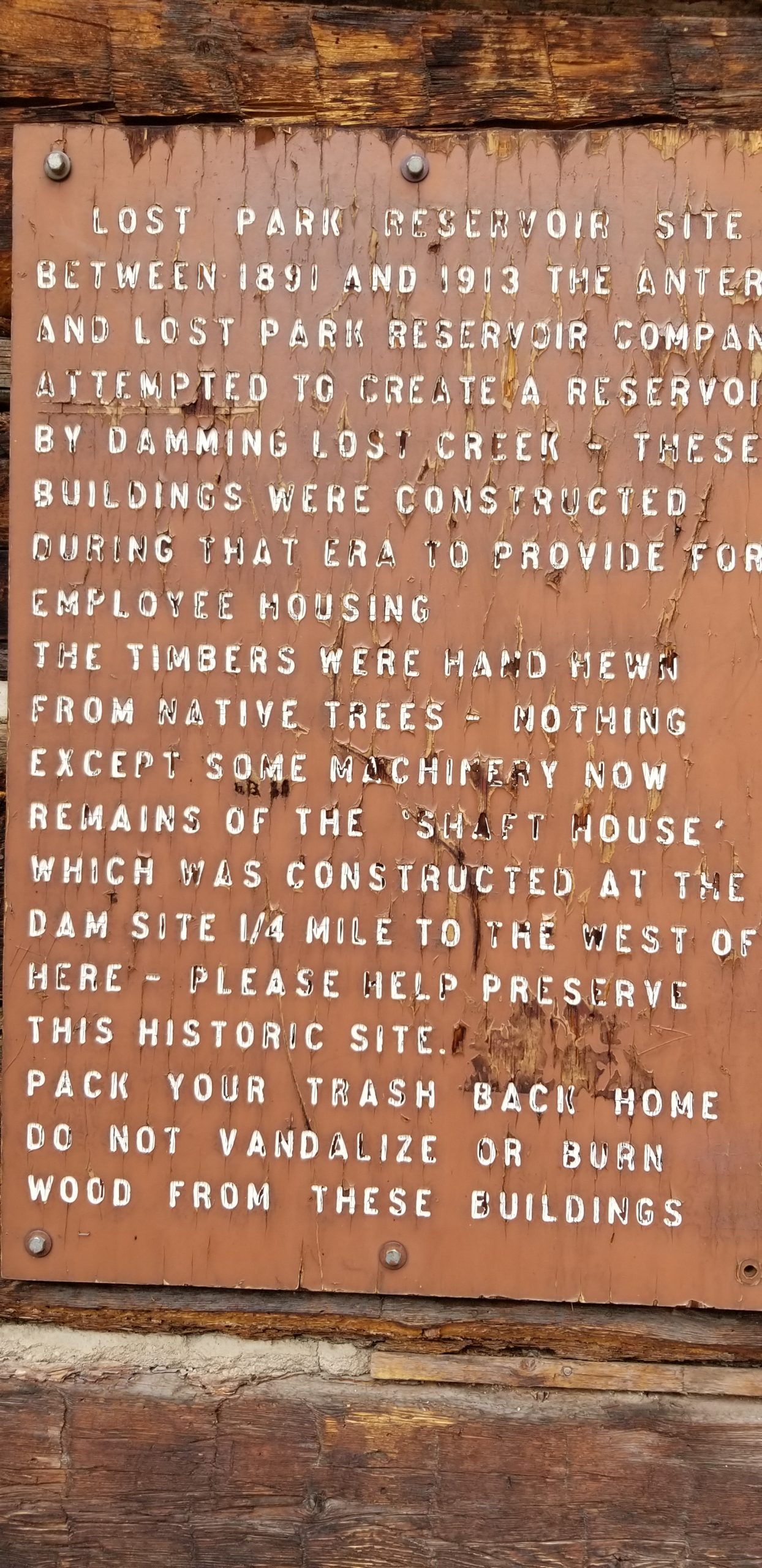

Posted on one is a badly aging sign, explaining the cabins are leftovers from long-ago efforts to build the Lost Park reservoir nearby. You can peer inside and almost imagine a group of weary workmen sitting around the fireplace, perhaps enjoying a nightcap or three.

Another ghost awaits about a 30-minute walk further east.

Best to leave your pack near the cabins, be glad your spouse is a good sport, and hit the spur trail that winds up and through more elephantine granite formations. There it rises to a rock shelf, where the sole remains of a shafthouse — a rusting iron cylinder once part of the machinery to lower men and equipment into the natural rock caverns below — leave the imagination reeling.

The first thing that strikes me: What on earth were they thinking? Building a reservoir back here? I hope they had a hardy team of mules.

A pioneer’s life of tragedy and success

A little bit of research turns up some fascinating bits, and a story that eventually includes Denver Water.

The Lost Park Reservoir was originally the vision of a Denver pioneer, Cyrus G. Richardson. Born in Maine, Richardson eventually wound up in Denver, seeking a more favorable climate for health reasons, at age 28.

His life was pockmarked with tragedy.

Prior to arriving in Colorado, all four of his children from his wife, Julia, perished. In an unimaginable turn, his three daughters all died within one week of diphtheria, a bacterial disease now commonly addressed with childhood vaccinations.

Despite such terrible loss, the couple moved forward with great success.

In the 1870s, Richardson settled into an office at 15th and Lawrence streets in downtown Denver.

From there he ran two ranches, a reservoir company and a law firm in partnership with his nephew. His real estate legacy remains visible today, with reservoirs he built for his ranches now at the center of the Marjorie Perry Nature Preserve in Greenwood Village and the Bluff Lake Nature Center in the Central Park neighborhood.

His contributions to the region are linked to what is now a civic landmark that winds its way through the metro area: the High Line Canal.

Unhappy with the volume of water in the canal in the late 1800s, he procured the land in the South Platte River Basin for what is now Denver Water’s Antero Reservoir in Park County.

He also envisioned the Lost Park reservoir and set about work on it in the 1890s.

But the Lost Park site proved challenging.

Just for starters, the terrain was far more rugged than Antero, located on wind-swept flatlands west of Fairplay.

Richardson’s plans for the Lost Park reservoir would depend upon a series of natural rock formations, in what is now part of the Pike National Forest, as the basis for a dam that would back up water that flows from the Kenosha Mountains and the Tarryall Range.

Richardson died before his visions for the Antero and Lost Park reservoirs were completed, at age 53 in 1894. But his concept lived on.

A granite puzzle and a mysterious creek

I first discovered Richardson’s name in a 1937 report about the Lost Park reservoir written by Denver Water’s then chief engineer Dwight D. Gross (for whom Gross Reservoir in Boulder County is named).

Gross reported that Richardson sunk a shaft 180 feet deep into the rock maze that blocks the valley and was intended to form the Lost Park reservoir.

This must have been part of the work performed by those dogged men who slept in the now-deteriorating cabins nearby. The shaft would have allowed men to examine the granite boulders and better determine the elusive path the water followed and how they might fill the spaces between boulders that would otherwise allow water to flow through.

Gross’s report notes that work stopped after Richardson’s death, and nothing more occurred until 1907, when the Antero and Lost Park Reservoir Co. purchased the property.

Workers in that period worked in the hidden riverbed, below the big boulders, excavating some of the area to allow a foundation to be laid for “core wall” that would form the heart of a dam.

Gross’s report, however, suggests they didn’t get very far. Instead of cutting away rocks to permit the installation of a wall, “the operation would be better described by saying they chinked or filled the spaces between the boulders with concrete.”

In 1924, Denver Water acquired the property for $150,000, with a legal decree to store 45,000 acre feet. That’s a lot of water, more than the current capacity of Gross Reservoir. Or think about twice the size of Marston, the hefty reservoir adjacent to a Denver Water treatment plant in southwest Denver.

A closer look into the labyrinth

Seven years later, engineers began investigating the Lost Park site more closely.

They rebuilt the collapsed shaft originally erected by Richardson some 40 years earlier. Workers found openings left in the shaft allowing them to exit at different elevations and explore the canyon and caverns hidden within.

They discovered a crude outlet works, with valves and pipes, had been constructed to control the flow of water from the future dam. But the equipment had deteriorated, and water readily found its way around the old construction, part of the confounding nature of the mysterious waterway.

Simply trying to follow the path of the water downstream under the massive boulders visible from the surface had men crawling over, under and around rocks. And following the water back upstream proved impossible, with deep pools too risky to explore.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, this elusive waterway is why the area is called the “Lost Creek” wilderness. The creek literally becomes lost under the labyrinth of granite boulders.

Even detailed topographic maps make no effort to map the whole stream. It shows up as disconnected blue line segments, indicating stretches where it emerges from its hidden pathway only to vanish again.

The 1937 report from Gross, the Denver Water engineer, still left open the possibility of building the reservoir. It called for excavating a trench through the boulders, building a core wall 190 feet high, and then adding another wall on top of that, extending above the rock field.

But by 1944, the reservoir’s prospects were fading.

Water rights engineer H.L. Potts, in a 1944 report about the proposed reservoir, described the city of Denver’s purchase of the Lost Park site as “the tail going with the hide,” implying it was thrown in as part of the more important purchase of Antero Reservoir and the High Line Canal.

A companion report, also from Potts, described the potential dam there as extending 2,800 feet across the valley and 330 feet in height, almost as tall as today’s Gross Reservoir. And for good measure, a massive tunnel drilled into the side of the valley to act as an outlet works.

Crazy stuff, I thought. Way back here, in what is now one of the state’s most popular wilderness areas.

These days, Denver Water still owns 310 acres of the old reservoir site and continues talking with the U.S. Forest Service on a possible land exchange, perhaps for parcels closer to an operating facility.

Lessons from the ghosts

We’d set up camp about three miles back down the trail, so after crawling around the old dam site for a couple of hours, we turned back, looking forward to pasta and whiskey under the stars — after all, we’d earned those calories.

It is, truly, one of the joys of backpacking: Big hikes mean big meals.

As we hiked back to our campsite, I kept thinking of the ghosts, the men who must have lived back here for weeks or months, building cabins, erecting machinery, crawling over rocks in caverns far below the surface.

They surely forged friendships, probably brawled, drank a lot, probably got hurt or even killed on or off the job.

Later, when I learned about Cyrus Richardson, and all the life he crammed into 50 years and the ambition it must have required to think he could develop a reservoir up here, it only elevated the respect I’ve long had for Colorado's pioneers.

It reminded me how much we take for granted our collective inheritance — even as we may not mean to do so.

So, the Lost Park reservoir never came to be. It’s easy to argue that was for the best. After all, its absence provides us a marvelous wilderness to escape to and explore.

I think the ghosts in the wilderness tell us something more, though. They’re not just sharing the fading clues to an ill-fated project.

I can hear them saying something else: “Look what we tried to do here. Audacious, right? Some of our efforts worked, some of them did not. But we took a stab.”

I like to think they’re asking us a question too:

What echoes might we leave for folks 150 years from now?