Disinfection saves lives

A century ago — and still, in many developing countries — people died a quick and horrid death after drinking contaminated water.

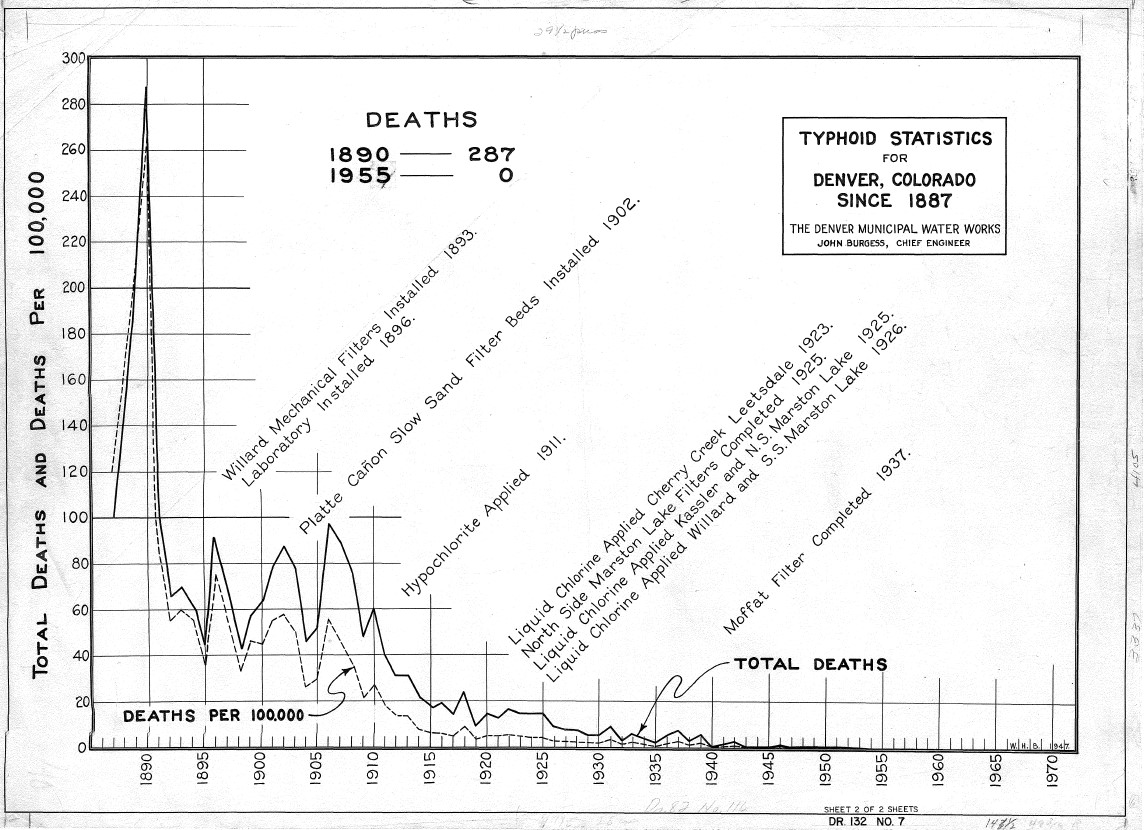

They got cholera, typhoid and dysentery. They vomited and cramped and had diarrhea until the end (remember Oregon Trail?). Then water providers started disinfecting drinking water by adding chemicals. The death rates from those water-borne diseases plummeted.

“Water treatment and disinfection save lives,” said Nicole Poncelet-Johnson, Denver Water’s director of water quality and treatment.

Yet with the good, comes a trace amount of bad. Sometimes, the combination of disinfection chemicals and naturally occurring organics can cause miniscule amounts of byproducts in all drinking water, including bottled water. These byproducts have intense-sounding names like chloroform and bromodichloromethane, and they’ve caused people to worry about long-term exposure.

For years, scientists around the world have studied disinfection byproducts and have developed ways to minimize their presence in drinking water. They’ve found that at high levels, these byproducts can be carcinogenic. But at such trace levels, the chance of someone developing cancer from drinking cleaned water over the course of 70 years is almost negligible.

And yet, in developing countries where treatment is unavailable, water-borne illnesses are still a leading cause of infant and childhood death. That risk, says the CDC, is “far greater than the relatively small risk of cancer in old age.”

“We don’t realize how good we have it in this country,” Poncelet-Johnson said. “We worry about the one in a million chance of developing cancer because you actually made it to old age. In countries that don’t disinfect, many kids die before they’re 6.”

That happened 150 years ago in Denver. Most of the water was delivered via open ditches, and residents worried that loose pigs were contaminating their drinking water. Absent disinfectants, city government had to do the next best thing. Banish the pigs.

Fortunately, today, outlawing livestock is not our only option. Each year, Denver Water takes more than 35,000 samples and performs nearly 70,000 tests to ensure your water is safe to drink — more tests than required by federal law.

Denver Water’s scientists test for regulated contaminants, such as disinfection byproducts, as well as nonregulated substances, such as hormones and pesticides. They use that data to make sure tap water is as safe as possible. It can inform how we manage the watershed or if we need to tweak the amount of chemicals used to clean tap water.

And we’re transparent about what’s in your water. Water quality reports are available each year, and they show that any measurable amounts of disinfection byproducts in Denver’s supply are always well within all recommended levels set by local, state and federal agencies, as well as by the World Health Organization.

On top of our advanced treatment practices, Denver Water is fortunate to use mountain snowmelt, source water that’s so pristine, it doesn’t contain a whole lot of naturally occurring organics that can bind with chemicals to create disinfection byproducts.

Most important, perhaps, is that your water is monitored constantly, and regulations are updated regularly, by scientists — the same people who go home to drink the water they monitor.

“We have some of the best water anywhere,” Poncelet-Johnson said. “We’re very lucky.”