Getting runoff ready in Summit County

Spring is a critical time for Summit County residents and Denver Water customers. It’s when snow starts melting, which helps fill Dillon Reservoir. But large amounts of snow melting too fast can lead to flooding and hazardous water conditions on rivers and streams throughout the county.

“Whether there’s a lot of snow or a little snow, we want residents and visitors to be aware that flooding is always a risk during runoff season, so they should be prepared,” said Brian Bovaird, emergency management director in Summit County. “Luckily, flooding doesn’t happen every year. But if we have a lot of snow, warm weather and heavy rain, we’re more likely to see flooding in the county.”

Denver Water plays an important role during runoff season in Summit County because operations at Dillon Dam have an impact on Blue River water levels, Front Range water supply, recreation and tourism.

“Our primary goal during the runoff is to fill the reservoir for Front Range water supply,” said Nathan Elder, water resources manager at Denver Water. “We also try to get as many benefits out of every drop of water for recreation, hydropower and the environment while trying to mitigate flooding in communities downstream.”

Summit County has more than 1,000 properties in regulatory floodplains — some of which are below Dillon Dam — according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The county also is home to many recreational trails around Breckenridge, Frisco, Dillon and Silverthorne that provide access to walking, biking and fishing along rivers and creeks.

“We do our best to minimize high flows out of the dam,” Elder said. “But because the goal of Dillon Reservoir is to provide water storage and not flood control, coupled with the range of variables factored into spring runoff and the likelihood of more extreme weather in the future, we can’t guarantee that we can prevent flooding every year, or with every big storm. That’s why we want people to be prepared.”

Dillon Dam history

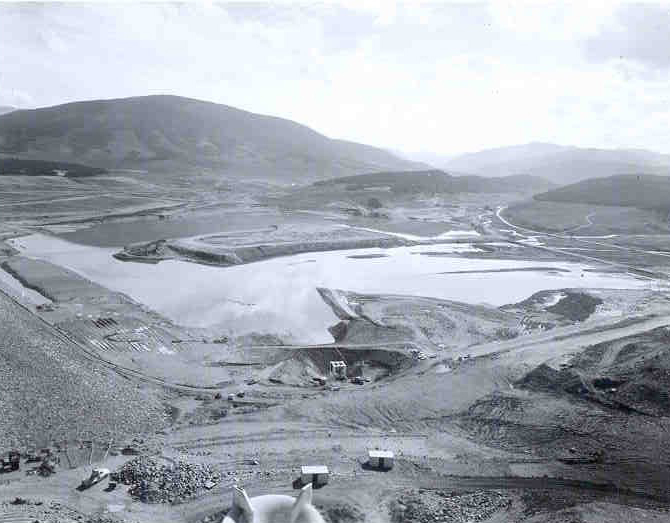

Understanding Denver Water’s role in Summit County begins with a look at the history of Dillon Reservoir.

Denver Water acquired water rights in Summit County in 1946 and built Dillon Dam in the 1960s to store water for Denver’s growing population.

As part of the project, Denver Water bought the entire town of Dillon and relocated it before filling the reservoir. The rest of the area around the reservoir was primarily rural ranchland.

Water from the Blue River, the Snake River and Tenmile Creek flow into Dillon Reservoir, which is a key part of Denver Water’s collection system that now supplies water to 1.4 million people — one quarter of the state of Colorado’s population.

The reservoir’s water level follows a cyclical pattern through the year, rising as snow melts in the spring and dropping through the summer, fall and winter months as the stored water is used to meet Denver’s water demand.

From an operational standpoint, Denver Water opens and closes valves at Dillon Reservoir to control how much water from the tributaries gets stored in the reservoir, how much flows through the dam’s outlet pipes into the Blue River and how much water is sent to Denver through the Roberts Tunnel.

Roberts Tunnel, 23 miles long, carries water from Dillon Reservoir, under the Continental Divide to the South Platte River. From there, the water ultimately flows into Denver Water’s Foothills and Marston treatment plants on the Front Range.

Complexities of running Dillon Dam

Dillon Reservoir’s primary function is to store water to be used by Denver Water customers. But Denver Water also tries to meet two secondary objectives: trying to keep the reservoir’s water level at a point that allows marinas in Dillon and Frisco to operate from mid-June through Labor Day, and trying to minimize the likelihood of high flows out of the dam.

To minimize the risk of high flows in years of concern, Denver Water can potentially release some water from Dillon before the snow melts above the reservoir to create more storage space. This allows the reservoir to capture larger springtime flows, helping to alleviate some of the high flows on the river downstream during this time.

But there’s a catch.

“Releasing water too soon based on runoff projections means we could miss a chance to fill the reservoir,” Elder said. “It’s a delicate balance because if the runoff ends up being below expectations, we could jeopardize prime water levels for boating and Denver Water’s ability to have a reliable water supply for our customers.”

Additional factors that play a role in managing Dillon include complying with downstream water rights obligations, optimizing river levels for rafting and fishing and adapting to weather conditions.

“We look at water supply first, and then try to get additional benefits,” Elder said. “Some decisions have to be made within hours, others are planned months in advance.”

Water storage dam versus flood control

All dams are managed for a specific purpose and Dillon Dam’s primary purpose is to store water for municipal water supply, not to hold back floodwaters.

“As a water supply dam, we aim to keep Dillon as full as possible, so we have the maximum amount of water in storage for our customers,” Elder said.

Chatfield Dam near Littleton is an example of a flood-control facility. The Army Corps of Engineers keeps the water level relatively low so there is space available in case of a torrential rain storm.

“Chatfield Dam was built to prevent disasters like the South Platte River flood that caused major damage in Denver back in 1965,” said Casey Dick, dam safety engineer at Denver Water. “Having extra space available allows Chatfield to hold back large amounts of water that can then be gradually released downstream.”

Climate change’s impact on water management

Another factor complicating Dillon Reservoir’s future operations is wider variation in weather patterns related to climate change.

“We’re seeing more variation in year-to-year stream runoff, including earlier runoff, more frequent and intense storms and more dramatic swings between wet and dry years,” said Laurna Kaatz, climate program manager at Denver Water.

A 2014 study conducted by the Colorado Water Conservation Board found that since the 1960s, Colorado’s climate has gotten 2.5 degrees warmer. The study was done to help water providers plan for the future.

Extreme weather events, such as storms that drop large amounts of rain in short periods of time, are the biggest concern in terms of flood risk.

“If an extreme rainstorm hits when there is a significant amount of snow in the mountains, it could cause rapid snowmelt into Dillon and increase the chances for flooding downstream,” Kaatz said. “The uncertainty of climate change is going to make operating decisions more difficult at Dillon Dam.”

The effects of the mountain pine beetle epidemic in Summit County, which was exacerbated by climate change, add further challenges. There are fewer trees to absorb snowmelt and a greatly diminished tree canopy to protect the snowpack from sun. This means runoff can occur at an accelerated rate over a shorter period of time, relative to pre-epidemic forest conditions, which helped to moderate peak flows.

Past high flow record

The amount of water that flows into Dillon from its three tributaries varies annually, as does the reservoir’s water level during spring runoff. Both variables play a significant role in whether there are high flows out of Dillon Dam in any given year.

Since 1965 when the reservoir first filled, the peak amount of water flowing into the reservoir during the spring runoff has ranged from a low of 410 cubic feet per second to a high of 3,408 cubic feet per second. (Think of one cubic foot per second as approximately 450 gallons of water flowing into the reservoir in one minute.)

The low point occurred during the drought year of 2012, while the high peak happened in 1995, following a particularly snowy winter and rainy spring. The median peak inflow into Dillon Reservoir during the runoff season is 1,750 cubic feet per second.

“In 1995, the reservoir level was a bit below normal and we were able to alleviate some of the high flows out of Dillon Dam by capturing and holding that water,” Elder said. “If the reservoir had been full, all that water would have passed through the dam’s overflow spillway and into the river below, so it’s a good example of the type of runoff conditions possible.”

To put the impact of high water through Silverthorne in perspective, FEMA designates 2,500 cubic feet per second as a 10-year flood level just below Dillon Dam, while 3,350 cubic feet per second at the same spot is considered the level of a 100-year flood.

Knowing the snow

Making it more difficult to manage Dillon Reservoir’s water is the challenge of getting accurate predictions of how much snow is in the mountains, how much water is in the snow, how much of that water will flow into the reservoir and when that will happen.

“The snowpack and streamflow monitoring systems available today rely on outdated methodology and provide only estimates of the water supply in the mountains,” said Cindy Brady, water resources engineer at Denver Water.

An example of the challenges of water management occurred in 2018, when snowpack measurements above Dillon were 117% of normal, but the amount of water that made it to the reservoir ended up being only 73% of normal.

“Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know exactly how much water will come down the mountains every year or when it will come down. That’s what makes managing a reservoir so tough,” Brady said.

Raising awareness

During runoff season, Denver Water sends daily and weekly updates about Dillon Reservoir’s water level, stream flows and water releases to stakeholders in Summit County so they can plan for high flows and alert the public about conditions.

“Living in the mountains with all the snow and streams, flooding is always a possibility,” Bovaird said. “Dillon Dam is one of five dams in Summit County that has infrastructure and homes below the dam, so we work closely with all the dam operators, including Denver Water, to keep people informed.”

Summit County Emergency Management provides a runoff season guide, which includes swift-water safety tips, flood preparedness and FEMA insurance information for property owners. The county also encourages residents and visitors to sign up for its Summit County Alert system to receive warnings about hazardous conditions.

“We provide sandbags for free every spring, and the county posts updates on its emergency blog and Twitter during active incidents,” Bovaird said. “The county also uses a public alert system similar to Amber Alerts if flooding is posing serious threats to public safety.”

In preparation and during runoff season, Summit County’s public works department removes debris and obstructions from waterways and culverts so high water doesn’t back up. Warning signs are also posted along walkways and streets along rivers and streams if water levels are rising.

The public can also get updates on water conditions by signing up for Denver Water’s free Dillon Outflow Update e-newsletter.