Mountain snowpack ‘looking good’ heading into spring

As Colorado copes with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is some reassuring news coming out of the mountains, where the snowpack is looking good heading into the runoff season.

Mountain snow, as it melts, fills Denver Water’s reservoirs, the main supply of water to 1.5 million people in Denver and several surrounding suburbs.

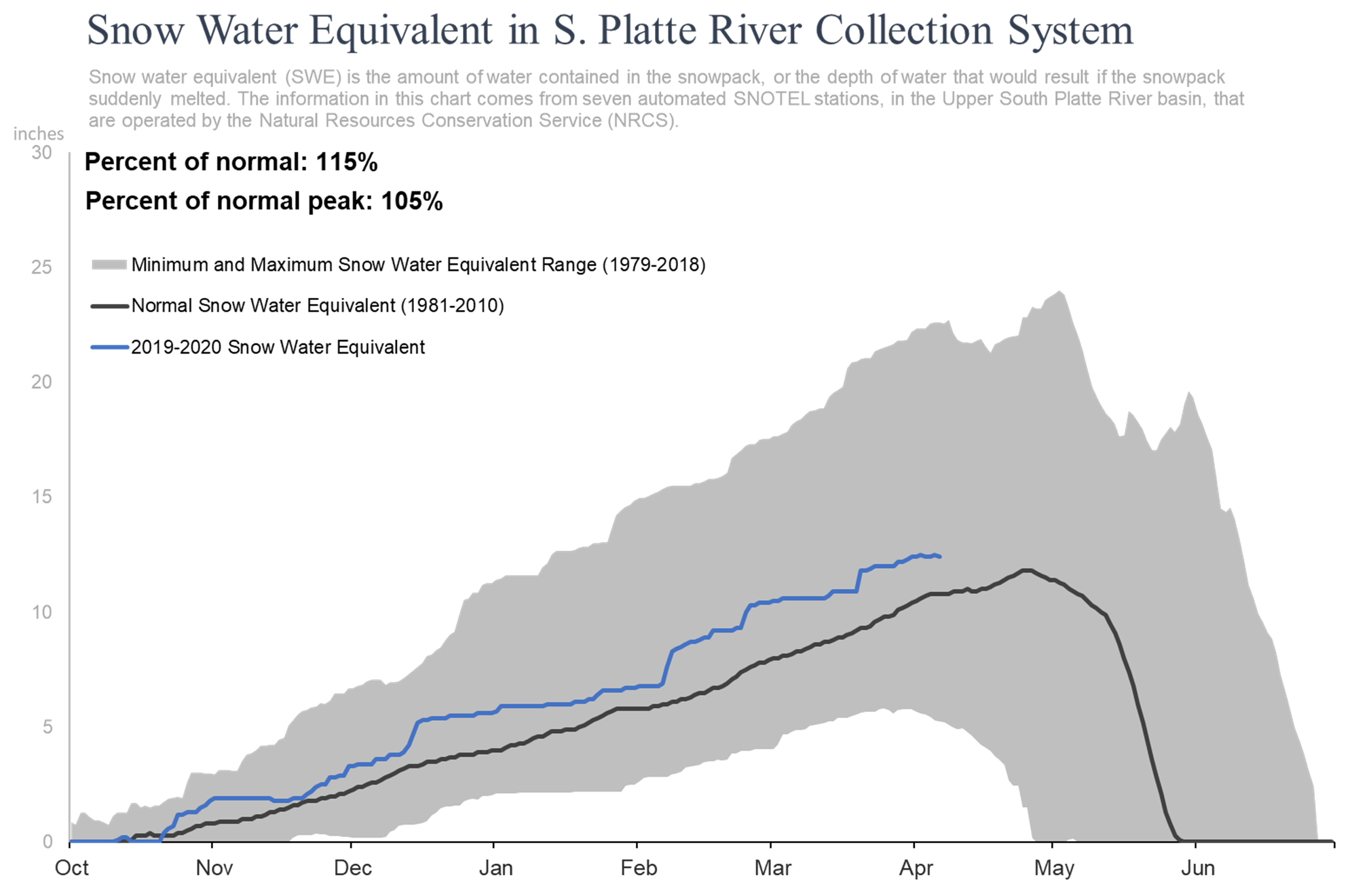

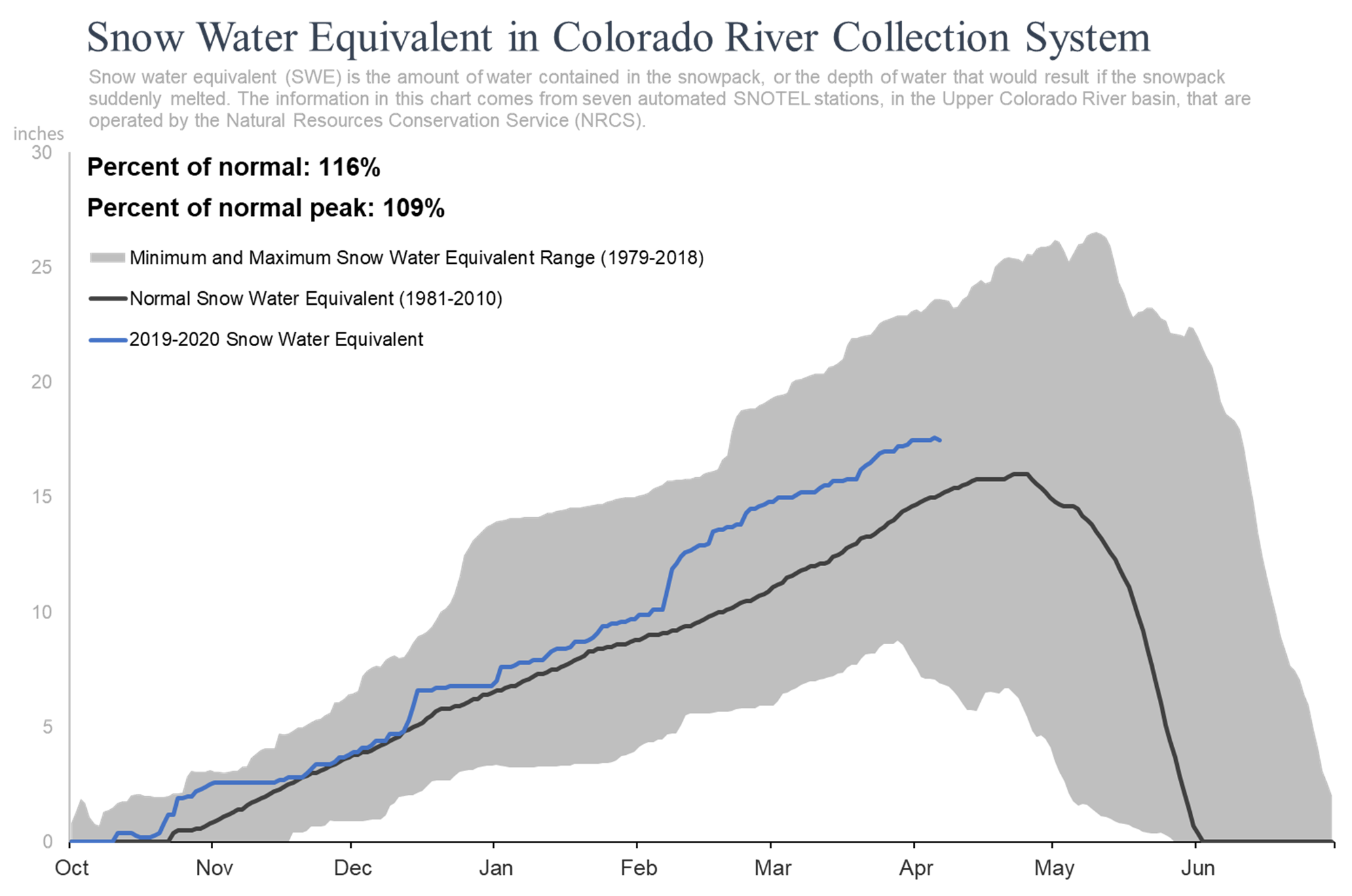

As of April 6, the snowpack in the Upper South Platte and Upper Colorado River basins, where Denver Water collects its water supply, stood at 115% and 116% respectively.

“Snowpack is looking good and we’re anticipating our reservoirs will fill when the snow starts to melt later this spring,” said Nathan Elder, water supply manager at Denver Water.

The snow season started strong with well-above normal snowfall in October. But while March is typically the snowiest month of the year, that was not the case this year.

“February was our biggest month across the central mountains so far this year,” Elder said. “About 30% of our total snowpack came from storms in February, that’s about double the average amount of precipitation for that month.”

Denver Water’s primary collection area includes the mountain peaks in Grand, Park and Summit counties, near the towns of Breckenridge, Fairplay and Winter Park.

Elder said the snowpack in those areas typically reaches its peak around April 23.

“April and May can still bring significant storms and the snowpack can change quickly,” Elder said. “But based on the last several months, we know this is going to be, overall, an above-normal snow year.”

Reservoir levels

As of April 6, Denver Water’s Dillon Reservoir was 90% full, according to Elder.

“We are fairly confident it will reach capacity this season, and that’s good news, since it’s Denver Water’s largest reservoir,” Elder said.

The utility’s other key reservoirs are Cheesman, near Deckers, and Gross, west of Boulder. As of April 6, those two reservoirs were at 70% and 48% of capacity, respectively.

Elder said both are likely to fill as well during the spring runoff.

Reservoir cycle

Denver Water relies on mountain snow for 80% of its water supply, with rain supplying the rest. When the snow melts, the water tumbles down rivers and streams that flow into reservoirs, where it is stored until needed in the metro area.

Reservoir levels, the gauge of how much water is in the reservoir, follow an annual cycle.

Levels drop to their lowest point around April 1, then begin to rise as the snow melts. The reservoir typically fills by July 1.

Then, as customers use water in the metro area, reservoir levels slowly drop through the summer, fall and winter months until melting snow once again fills the reservoirs the following spring.

Computer models and projections

Each spring, Denver Water’s planners run computer models to project how much snowmelt will end up in the reservoirs in coming weeks.

These projections are critical, because the amount of water that’s available affects municipal and agricultural water supplies as well as recreation on rivers and reservoirs, fish habitat and the potential for flooding in communities located near rivers and streams.

The models use weather outlooks, streamflow forecasts, water rights and current reservoir storage levels. Streamflow forecasts are important because dry soil can absorb some moisture before it reaches mountain streams.

This year, despite snowpack being above normal at 115%, streamflow forecasts throughout the collections system are close to 100% of normal, which is another good sign that the reservoirs will fill in the spring.