Finding her identity as an Asian American

Denver Water is very proud of our diverse workforce. We asked a few of our employees to share their culture and experiences for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, which occurs in May and celebrates the achievements and contributions of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.

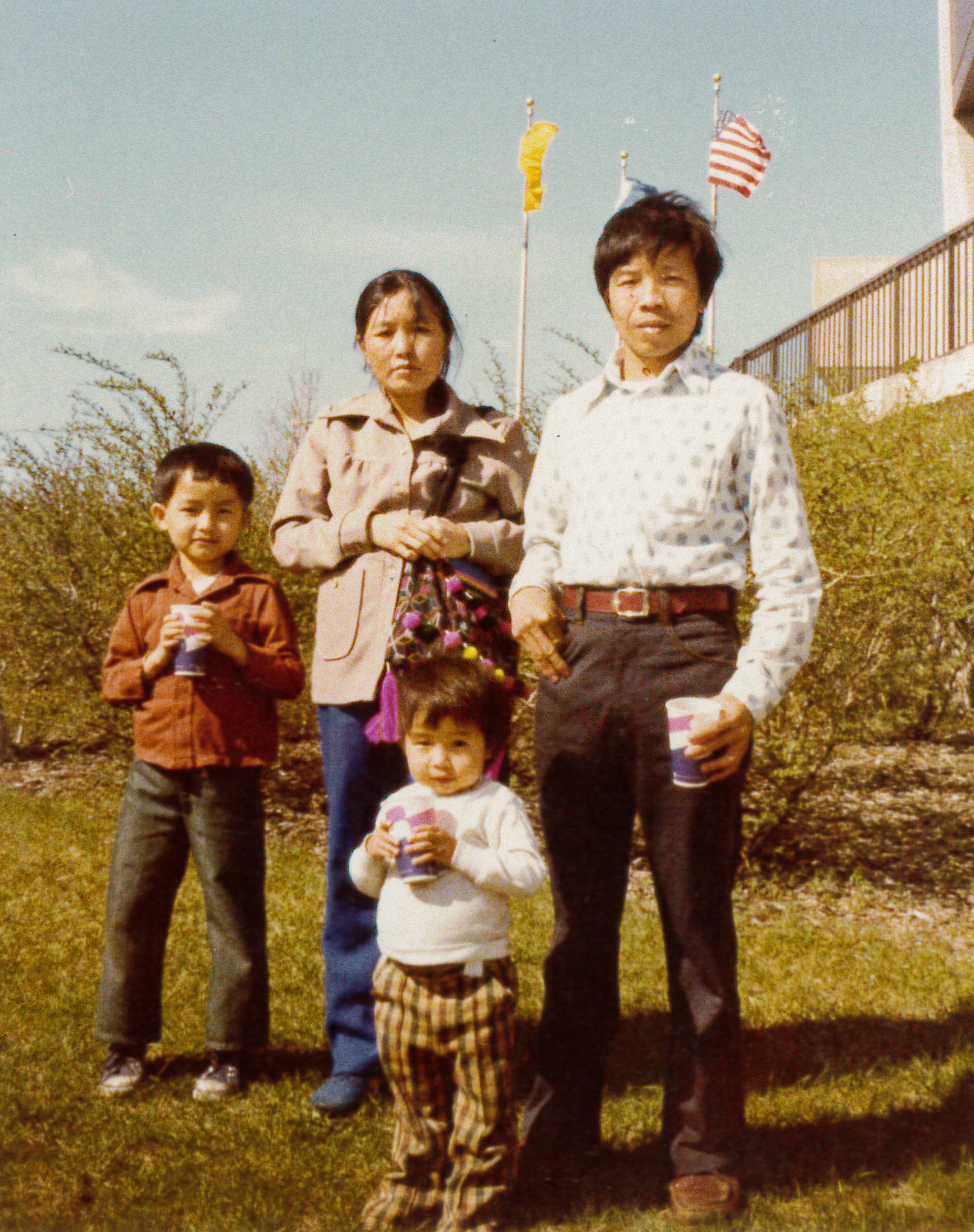

Yua Cha was born in a Hmong refugee camp in Thailand.

When she came to the U.S. at age 2, neither she nor her family spoke English.

They got off the plane in St. Paul, Minnesota, with all that they had — clothing and sandals.

Today, Cha heads up Denver Water’s procurement team, the group responsible for buying and contracting goods and services for the utility that supplies drinking water to 1.4 million people across the metro area.

It wasn’t always a smooth journey.

Cha remembers struggling to find her identity as she balanced the expectations of being a Hmong girl with her desire to be an average American kid. It wasn’t until she went to college that Cha began to appreciate her Hmong culture and the bravery her parents demonstrated in coming to America.

“One of the proudest moments in my life was when I was able to show my parents my office when I got my first management job; to show them the outcome of their sacrifice,” Cha said.

Cha's family, which includes eight siblings, is Hmong, a people who lived in the hills of South China before migrating to the mountains of Laos in Southeast Asia.

Viewed as traitors after acting as secret agents to America during the Vietnam War, the Hmong fled Laos in large numbers for protection when the war ended. Finding a neutral place to settle in Thailand, they lived in refugee camps, living off the land. Many also applied for permission to come to the United States.

Cha was born in one of those refugee camps in Thailand and spent her first two years there with her parents and older brother, Chia.

Then, the family learned they were authorized to immigrate to the United States.

Cha’s parents did not have a plan and didn’t know where they would live, yet they never considered staying in Thailand nor feared what awaited them in America.

A migratory people by nature, Cha’s parents approached their move to the U.S. like previous moves in their lives. They would migrate with their large Hmong community, as they believed there was safety in numbers.

For Cha, who thoroughly researches and plans as much as possible before making an informed decision, this approach seems daunting.

“For my parents, a plan wasn’t practical because survival and safety was the priority. They always figured out a way to make things work with what they had, no matter where they were located,” she said.

The family was packed into a vehicle with other refugees and made the long, eight-hour drive from the camp to the airport in Bangkok, bringing what few possessions they had in a worn suitcase, including a small portion of rice and an empty plastic jug to hold water.

They landed in St. Paul, Minnesota, in December 1979, their light clothing and sandals offering little protection against the depths of the bitter winter.

Upon arrival, a Hmong translator introduced them to Betty and George Livingston. For the first time since they submitted their immigration application, they found out they had sponsors. With no other information, they were told to go with the Livingstons.

This was the last time they would have an interaction with another Hmong person for quite some time.

Language was an immediate barrier. Cha's parents did not speak any English and their sponsors did not know the Hmong language.

“I really can’t imagine how my parents must have felt landing in a foreign country, having been exposed to nothing outside of their tight-knit Hmong community, with no education and not being able to communicate with anyone,” said Cha.

“They had to learn so much, almost all of which we take for granted. Even simple things, like telling time, had to be taught.”

Cha's family stayed with the Livingstons for two months.

“They did everything for us, from getting us an apartment, to enrolling us in school to helping my father get a job. My parents wouldn’t have known what to do without them,” said Cha.

The Livingstons, who remain close friends, helped Cha's parents sign up for English classes and enrolled Cha’s brother, Chia, in school.

“My parents weren’t familiar with the concept of formal education, and despite George and Betty trying to pantomime that they were taking my brother to school, my parents had no idea where he went each day,” said Cha.

“Eventually, when he started speaking English, they made the connection that wherever he was going, he was learning.”

Cha and Chia became advocates for their parents.

“We didn’t realize it at the time, but they depended on us. We were only children, but we could speak English and helped them navigate the government, school and financial systems in the U.S. We weren’t aware at the time, but my parents had so much confidence in us to help them,” she said.

With each new experience, the family continued to adapt to American life.

Cha recalls her earliest memory of how Western culture impacted her.

“I remember when I was in first grade our assignment was to draw a self-portrait. I have dark hair and dark eyes, but I drew myself with blonde hair and blue eyes. The teacher pulled me aside, put me in front of a mirror and asked me, ‘What color are your eyes?’ I told her they were blue. I could tell she was appalled by my response and probably thought I was being defiant,” said Cha.

“As an adult, I can appreciate her reaction, but at that time, that’s how I saw myself. I was six years old. My perception of the world was not based on color, class or race. There were no people of other races living near us. Everyone was white. I wasn’t trying to be difficult; I simply didn’t see myself as being different,” she said.

Cha's parents raised her as a traditional Hmong girl, but as an adolescent she began to resent her culture’s gender inequalities.

In Hmong culture, girls and boys are raised differently. Girls are taught domestic chores, how to be proper and aren’t given as much freedom.

Cha remembers being a rebellious, sometimes difficult child. Because males had more liberties, she struggled with her cultural identity.

“My brother could go out and have freedom, but I had a 7 p.m. curfew. Although my parents raised me to be independent, I saw how girls were limited in my culture. I saw the restrictions that being Hmong placed on females and I resented being a part of that,” Cha said.

As she wrestled with her culture, the growing family moved to Sacramento when Cha was 12.

She had never seen so many people from different races before, yet it was in California that she began to see the impact of bias and racism.

“As I got older, I saw that others initially assessed me by my appearance. They saw an Asian female, and sometimes that influenced how they interacted with me.”

When Cha enrolled in school, the girl who grew up speaking English was automatically put with students who couldn’t speak the language.

“No one even asked me or tested me for class placement, they just assumed I couldn’t speak English,” said Cha. She’d spent years pushing away her Hmong culture, seeking to simply be an American girl, but despite her efforts found that many could only see her as Hmong.

It was in a college women’s studies class that Cha began to appreciate her experience.

“I finally saw all my own personal struggles reflected on a larger scale. I saw that I wasn’t alone.”

The class helped Cha explore her identity and the challenges she faced being a Hmong woman.

“As I get older, I have a greater appreciation for my Hmong culture. There are beautiful things about my heritage, and I want to maintain many of the Hmong values, like respecting elders, always taking care of family, being available to help and having honor and respect for myself.”

Cha reads all she can about Hmong history. She wants to learn the Hmong art of intricate embroidery and asks her parents to share their memories and personal experiences.

“When my parents tell stories about their move to the U.S., they chuckle at how naive they were and how little they knew. But I am so very grateful for their courage and the sacrifices they made for me and my eight siblings to give us the opportunities we have had.

“My parents have come a long way since they’ve moved to America, and I’ve come a long way in my own journey to figure out who I am as an Asian American."