Cloud seeding’s role in the winter season

Editor’s note: This story was posted in 2018 and includes comments from Joe Busto, a leader in Colorado’s cloud seeding efforts who passed away in December 2019. Denver Water and partners in the cloud seeding program are grateful for his leadership and support of the program for many years.

Ask any skier or snowboarder and they’ll tell you they’re looking for lots of fresh powder in the mountains this season.

In the fall of 2018, ski resorts welcomed a wave of snow-bearing storms, which also were good news for Colorado’s cloud-seeding operations.

Cloud seeding is a weather modification technique used across western Colorado to enhance snowfall, boosting mountain snowpack.

“Cloud seeding doesn’t make clouds, it’s about getting more snow out of a storm,” said Joe Busto, cloud seeding program manager with the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “We need good, juicy storms for the process to work effectively.”

The technique uses a propane-fired generator to send tiny particles of silver iodide into the sky. Winds lift the particles into the clouds where they attract water vapor, grow, and fall as snowflakes. Silver iodide is the industry standard material used in cloud seeding, and independent scientific studies have shown it to be environmentally safe to use for seeding operations.

“There are storm clouds that blow through Colorado that may have plenty of liquid, but not enough particles to form snowflakes,” Busto said. “What we’re doing is adding more particles into the clouds and using natural processes to harvest that water vapor and squeeze more snow out of a storm. Silver iodide is essentially a dust particle for cloud vapor to bond to.”

Cloud seeding is most effective in average-to-wet winters, when multiple storms loaded with moisture come through.

“The dry winters are when everyone hopes cloud seeding can help with the snow, but unfortunately that’s not how it works,” Busto said. “We gauge success by looking at snow totals over the years, not single seasons.”

The state Department of Natural Resources has permitted seven cloud-seeding programs in Colorado. Around 40 organizations typically spend roughly $1 million a year on the programs.

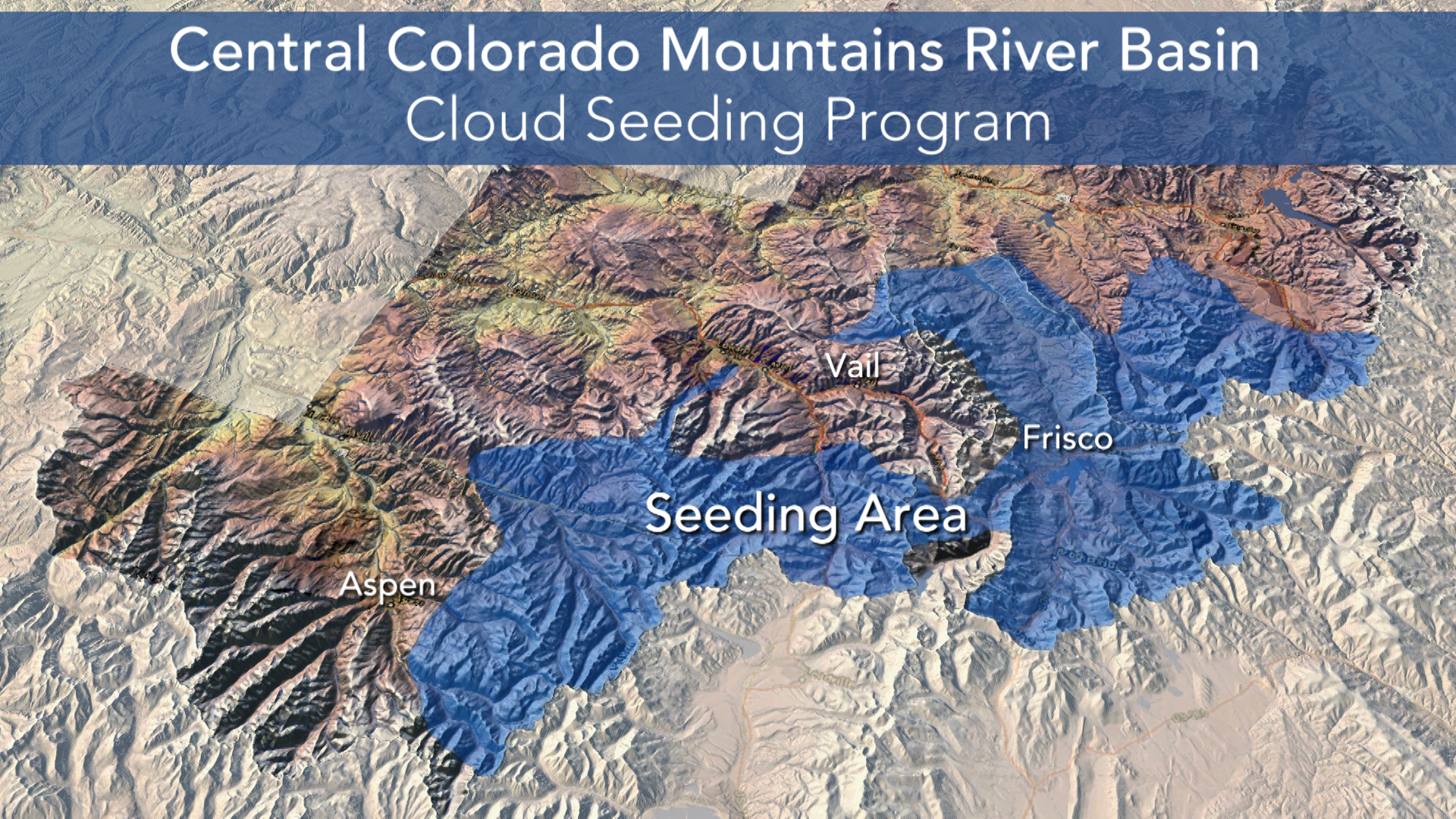

Since 2012, the Front Range Water Council has helped fund one of those programs: the Central Colorado Mountains River Basin Cloud Seeding Program.

The council includes Denver Water, Aurora Water, Board of Water Works of Pueblo, Colorado Springs Utilities, Northern Water, Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District and Twin Lakes Reservoir & Canal Company. Other partners in the program include the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the Colorado River Water Conservation District, ski areas and water utilities in Arizona, southern California and Nevada.

The partners pay for the operation and maintenance of four high-elevation remote control generators and more than 20 manually operated generators. The machines seed the clouds that pass over high-elevation portions of Eagle, Grand, Pitkin and Summit counties.

The generators are placed in strategic locations to boost snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Before cloud seeding can begin, specific weather conditions must be met, such as which way the wind is blowing, as well as the temperature and height of the clouds. Operators also focus on storms carrying large amounts of moisture. All operations are monitored and regulated by the state of Colorado.

Critics have questioned the effectiveness of cloud seeding in the past, but Busto points to independent scientific studies that show when conditions are right, cloud seeding can boost snowfall by 5 to 15 percent. That's roughly equal to getting an extra inch of snow out of a 10-inch snowstorm.

“You can’t seed every storm,” he said. “Only about 10 to 14 storms that pass through the state each winter meet the criteria.”

The dry winter of 2017-18 is an example of how dependent cloud seeding is on the existing weather conditions.

“Last winter, we planned to run generators for 2,000 hours in the target region. But, unfortunately, conditions were only favorable to seed for 1,200 hours,” said Dave Kanzer, deputy chief engineer at the Colorado River District and manager of the Central Colorado Mountains River Basin Cloud Seeding Program.

This season’s winter is off to a better start, according to Kanzer.

“We’ve already had six seedable storms this season and approximately 272 hours of seeding operations, so we’re above average for this time of year, and we are optimistic that we can make a positive difference for water suppliers, skiers and riders,” he said.

Desert Research Institute and Western Weather Consultants are the contractors for the operational seeding activities of the program. They also estimate the impact of the seeding operations using automated snow monitoring sites, ski resort data and weather models.

And it’s worked, according to reports prepared by Western Weather Consultants.

They say during years when conditions are ripe for cloud seeding, their operations have added an average of 60,000 acre-feet of water to the target area in the Upper Colorado River Basin.

“A couple inches here and there add up,” said Eric Hjermstad, field operations director at Western Weather. “If you consider 1 inch of extra snow spread across 300 square miles, that’s a big boost to the water supply.”

Denver Water participated in cloud-seeding programs in the early 1950s and 1980s and picked up again following the 2002-03 drought.

“Mountain snowpack provides 80 percent of our water supply,” said Dave Bennett, director of water resource strategy at Denver Water. “While it’s tough to pinpoint the exact impact of cloud seeding, Denver Water, the ski areas and our partners in the Front Range Water Council feel there is enough benefit to support the program.”

Since cloud seeding’s early days back in the mid-1900s, advancements in technology have dramatically improved cloud-seeding efforts, according to Busto.

One of the biggest advancements is the development of remote control cloud-seeding generators. Those machines can be placed at higher elevations, where they are closer to the clouds and thus more effective. They also don’t require someone to manually ignite hard-to-reach generators if a storm passes through in the middle of the night.

“This summer, two manually operated machines near Leadville and Beaver Creek were replaced with state-of-the art remote control generators,” Busto said. “Our goal is to continue adding more of these machines, so we can be more efficient with our seeding operations.”

Advancements in weather forecasting and monitoring have also improved.

New developments include high-resolution weather modeling, simulated weather balloon launches, ceilometers that measure cloud base, and radiometers that characterize super-cooled liquid water to help determine when to seed during a storm system.

“These advancements provide more up-to-date data,” Hjermstad said. “The more information we have about atmospheric conditions, the more efficient we can be about when to seed.”

While cloud seeding benefits water supply, ski resorts also get a boost. That’s why Breckenridge, Keystone and Winter Park ski areas help fund the program.

“We’ve been cloud seeding on and off over the past 30 years,” said Doug Laraby, planning director at Winter Park Ski Resort. “If we can add a few more inches, that’s great for skiers. And when the snow melts, it’s great for water supply.”

As cloud-seeding programs across the West advance, collaboration among Colorado River water users has grown. In 2018, Colorado, Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have agreed to cooperatively fund cloud-seeding programs for at least another nine years.

That’s because cloud seeding is an important element of the Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan, which aim to keep water levels as high as possible in drought-depleted lakes Powell and Mead and to help ensure the basin states remain in compliance with the Colorado River Compact.

“The cloud-seeding partnerships have never been stronger,” said Kanzer, of the Colorado River District. “We have great synergy with complementary and diverse contributions from both sides of the Continental Divide in Colorado and from across the entire Colorado River Basin to help meet the regional water supply needs of the future.”