Denver Water’s past, future meet at landmark hilltop

The hill at Loretto Heights in southwest Denver is home not only to one of the city’s most famous buildings, but also a unique part of Denver Water’s delivery system.

The hill is best known for the historic tower built in the 1890s as part of a boarding school and college. But buried under that same hill is a 575-foot-long concrete tunnel used to deliver water.

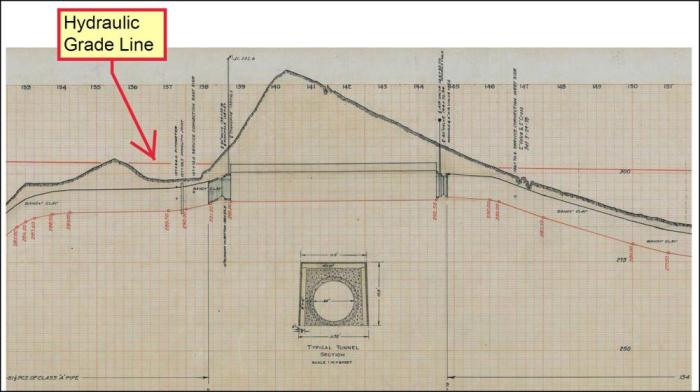

Denver Water built an 84-inch diameter tunnel through the hill in 1925 to solve a hydraulic challenge: How could they move water through a pipeline from the Marston Treatment Plant in southwest Denver and get it to go down a valley, up the Loretto Heights hill, and then on to downtown — without using a pump?

In this case, engineers used forces of gravity and pressure to “push” water through the pipeline and across the hills and valleys.

Denver Water’s Lead Reduction Program has surpassed 10,000 lines replaced, find out more.

But there was one catch — the pipeline could not go above what is called a “hydraulic grade line” — an elevation above which water moving through a pipeline loses too much pressure to keep moving efficiently.

The pipeline’s hydraulic grade line around Loretto Heights is roughly 5,479.5 feet above sea level, but the hill — which is one of the highest points in Denver — has an elevation of 5,510 feet.

So, to avoid going over the critical grade level, engineers had to go through the hill to solve their challenge and keep water moving.

“The engineers who built Denver Water’s system had many challenges they had to overcome to get water to the city,” said Garrick Thompson, design project engineer at Denver Water. “In this case, building a tunnel through the hill was the best option for this pipeline.”

While Denver Water has several tunnels in the mountains to move water, the Loretto Heights tunnel is the only one in the utility’s 335-square-mile metro area distribution system.

Watch a video slideshow of the construction of the tunnel in 1925:

Over the years, the tunnel developed signs of wear and tear, as did the large valves located on each end.

The tunnel had a number of cracks in the joints that needed to be repaired, according to Thompson.

The valve on the south end of the tunnel, where it enters the hill, leaked when it was closed and the valve on the north end of the tunnel, where it exits the hill, no longer opened or closed. Two additional valves, one on each end of the tunnel, were never put into operation and were no longer needed.

Watch a video of an inspection of the tunnel:

Valves play an important role on a pipeline. Operators open and close valves to control the flow of water through the pipe, sometimes stopping the flow of water completely to allow for inspections or repair work.

Thompson said the old Loretto Heights tunnel and valves were on Denver Water’s list of repair projects.

When construction on a new residential development at Loretto Heights began, Denver Water worked with the developer to do the needed upgrades and repairs before homes were built — and to avoid disrupting the new neighborhood later.

Work to repair Denver Water’s tunnel and replace the valves began in January.

After digging down to uncover pipes and valves installed a century ago, crews removed the four large, original valves, placed new pipes, installed a new valve, and repaired cracks inside the tunnel.

The engineering team determined that only one valve would be needed at the site, according to Thompson.

The new valve is the same diameter, but smaller in overall dimension and weight than the four original valves and will be easier to operate when water needs to be shut off on the pipeline.

Construction workers also repaired cracks inside the tunnel and installed 46 internal joint seals in areas where joints were cracking.

Primary work on the project wrapped up in April, with the pipeline cleaned and sanitized, returned to service and once again buried underground — hardly noticeable to the public and ready for the future.

“This project is an example of Denver Water’s proactive approach to pipeline and tunnel maintenance,” Thompson said. “These repairs and upgrades will keep this pipeline in service for many years and ensure a safe and reliable water supply for our customers.”

MORE PHOTOS BELOW