'Peak snowpack' can pack a surprise punch

April is a big month for water watchers. That’s when Colorado’s snowpack typically reaches its highest level before the big melt-out that follows.

The watchers call this moment “peak snowpack.” And it can be a useful measure to predict water supplies for the warm months to come.

Peak moments that fall earlier on the calendar can mean a spring runoff that ends too soon and reservoirs that don’t fill. Conversely, late peaks can mean reservoirs spill and high-water flows that can overtop riverbanks.

Indeed, a closer look at “peak” numbers over the last several decades reveals some big surprises when the timing of the maximum snowpack falls outside the late April norm. Such off-rhythm peaks can lead to watering limits or, in the other extreme, raging runoff that can do damage to land and property.

For Denver Water, this year’s peak snowpack numbers look good.

A mid-to-late April high point appears likely, and a healthy amount of water in the snow supports the utility’s forecast for full reservoirs for the upcoming irrigation season.

In short, it’s what Denver’s water watchers might call “a typical year.”

Join people with a passion for water, at denverwater.org/Careers.

In fact, though, the timing of the peak snowpack and how much frozen water the snow holds at that point is a highly variable condition and can leave water supply managers scrambling. This variability can be easy to forget when most years follow the script, or don’t veer far from it.

“As a water manager, if I only had one piece of data to determine how water supply was looking for a given year, it would be peak snowpack,” said Nathan Elder, who manages the tricky business of water supply for Denver Water.

“Snowpack peaks can be highly variable in quantity and timing, and those factors indicate what the runoff and water supply situation will look like.”

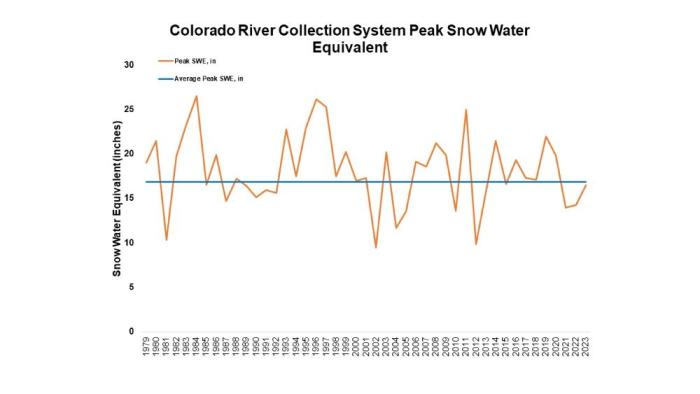

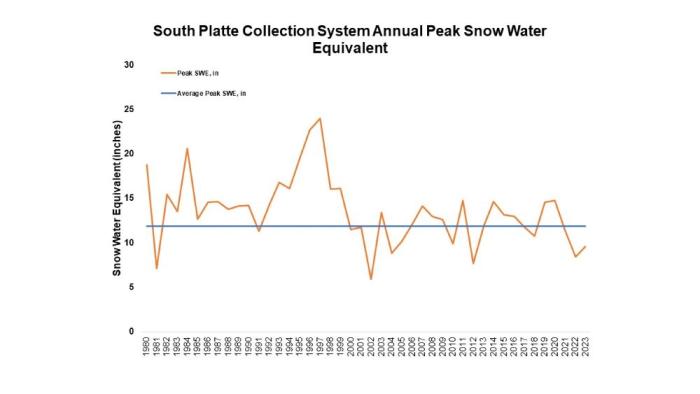

Take a look at the following graphs, which show the wide variability in the amount of water frozen in the snow at the point of “peak snowpack” over the past 45 years. The range in both the Colorado and South Platte river basins where Denver Water collects water can stretch from 10 inches to more than 25 inches of water in the snow.

Denver Water gets its water from parts of two major river basins — the South Platte and the Colorado. Both tend to hit peak snowpack in late April (the 23rd and the 25th respectively) and hit an average of about 12 and 17 inches of “snow-water equivalent,” or SWE, a fancy way of saying amount of water in the snowpack.

But some years Mother Nature has ignored those averages by frightening margins.

One of the scariest was 2012, when peak snowpack for Denver Water collection areas in both basins came not in mid-to-late April, but early March — March 5 in the South Platte and March 6 in the Colorado.

That was about seven weeks ahead of average and it forced Denver Water to implement outdoor restrictions as reservoirs failed to replenish.

Then there was the infamous spring of 2002, when snow-water totals for Denver Water collection areas at peak were a mere 50% of average in the South Platte Basin and 56% in the Colorado — another example, like 2012, of terrible numbers striking both of Denver Water’s collection basins in the same year.

Learn more about how Denver Water monitors the snowpack.

The spring 2002 peak snowpack contained some of the lowest amount of water in the snow over the last 45 years of records.

That early 2000s drought hung on until the following spring in 2003, when it was busted — fantastically and famously — with a late March blizzard that dropped 7 feet of wet snow in the foothills, 3 feet of snow in the city and put an end to 19 months of below-average precipitation in Denver.

“Liquid Gold,” blared the banner headline of the now-closed Rocky Mountain News. Anyone living in Denver more than 20 years remembers the storm.

Peak snowpack has also offered surprises on the opposite end of the spectrum, bringing late peaks and a wealth of water.

In 2015, the peak snowpack date in both basins came a month later than normal, on May 23. That meant a more compressed runoff season and flooding challenges, particularly along the South Platte.

Watch this video about the epic spring runoff of 2015:

In 1997, the South Platte’s peak snowpack hit a stunning 203% of average. In all, that was 24 inches of water in the snow, twice the average level in a basin that fills four major reservoirs for Denver Water.

Another mark experts like to track is date of melt-out — the date when the last of the snow melts at various measuring spots in the high country. In both basins that typically happens in early June. But, like peak snowpack, melt-out dates can surprise too.

Way back in 1981, a terribly dry year, the South Platte basin saw melt-out April 27 — about the time when Denver Water would typically see peak snowpack! Scary stuff.

Alas, in 1995, the South Platte went to different extremes, with the final melt recorded July 4, an entire month later than average.

In the Colorado River Basin, the latest such melt-out stretched to July 12, in 1983. That year is famous for the swollen river flows all the way to Lake Powell, where Glen Canyon Dam nearly overtopped.

That runoff season was memorialized in the "The Emerald Mile," a remarkable book that chronicled attempts to take advantage of record river flows to set speed records boating through the Grand Canyon.

All of it is a reminder that average years are just another way nature leaves room for surprises.

So, let’s be satisfied this spring with an “average” peak and a solid water supply for 2024.