The Pac-Man of water

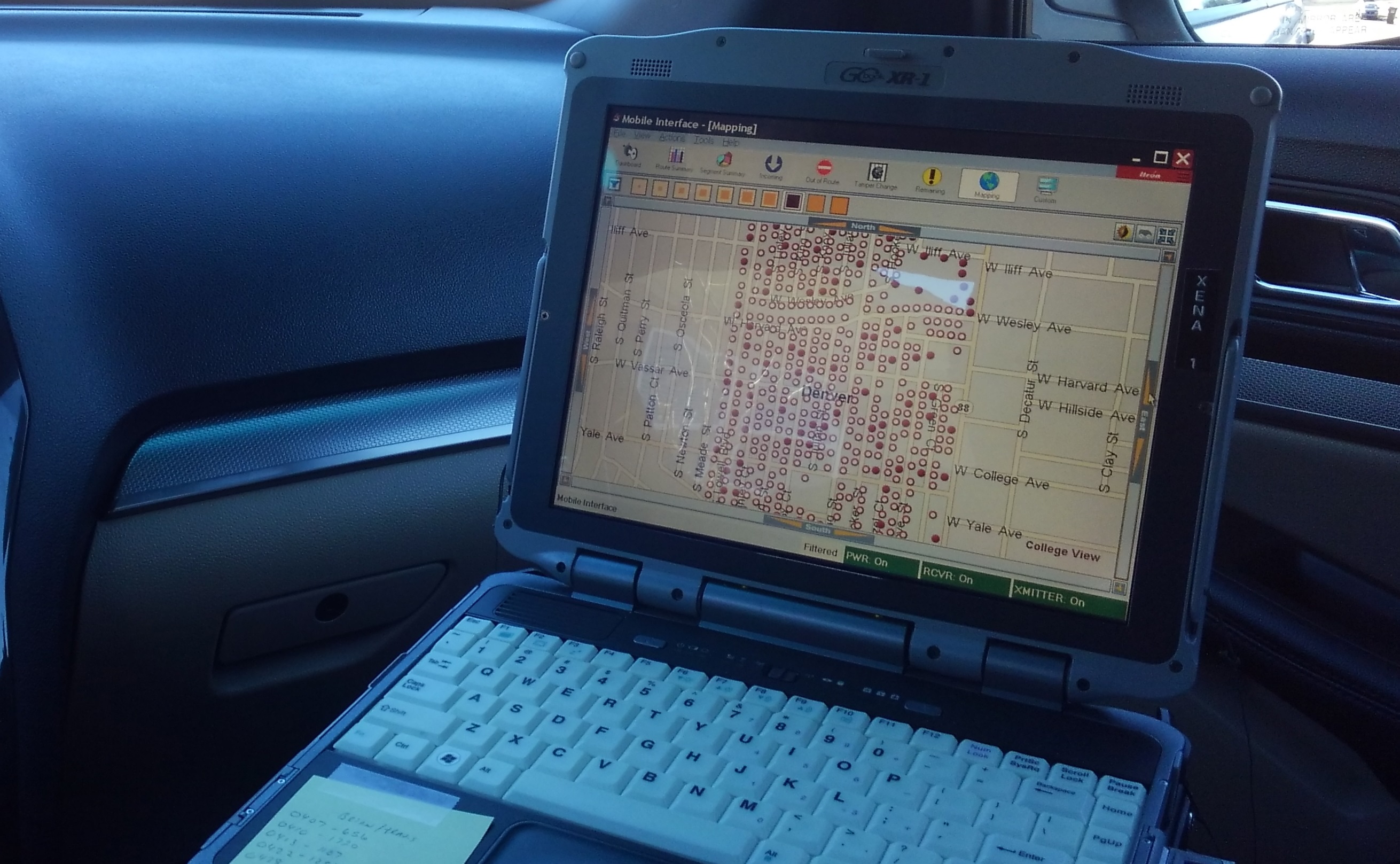

With the turn of a key, a computer stationed in the passenger seat of a meter reading vehicle powers up and soon the car echoes with the sound of constant pings, as Denver Water’s own version of Pac-Man comes alive.

This is Brian Holcomb’s office.

One of four meter readers, Holcomb spends the day navigating a Google-like map on his computer screen as he drives through Denver Water’s service area. The map is lined with tiny dots that he gobbles up as he drives past, indicating that the electronic signals from the meter at each property were captured.

When the dot goes away, the previous month’s water use from that property is automatically recorded and goes into the system for a bill to be sent out the very next day.

“It’s not as easy as just driving up and down the block — it takes strategy and knowledge of the area and equipment to capture each read as efficiently as possible,” said Holcomb. “Sometimes we’ll pick up a read from a block away, and other times it’s difficult to get a read when we’re sitting right in front of a house.”

That’s because each meter sends out a signal every 6-15 seconds with a range of 300 feet. But, if there is an interference — like a tree or vehicle — between the meter and the meter-reading vehicle when the radio signal goes out, the information may not be captured.

And, just like in Pac-Man, if a dot is missed, the readers go back and try to capture it.

“We know where the meters are at each location, and can use that to find the best spot in front of a house to try and capture an unregistered read,” said Holcomb. “But sometimes that doesn’t work, and we have to send a field tech out the next day to manually get the read for billing and fix the electronic device so we can capture the read by vehicle the next month.”

This job wasn’t always like a video game for Holcomb, who started as a meter reader in 2002. Prior to the current technology being installed on every meter in the service area by 2007, 36 meter readers walked the city blocks, stopping at each meter, opening the lids and manually reading each device.

Tom Graybeal, currently a water distribution foreman, started his career at Denver Water as a meter reader in the early 1980s. He said it was a much different job back in the day.

“Luckily, I was young. We had to deal with dogs, go in basements and even bring a shovel to dig out the meters during the winters,” said Graybeal. “One time, I opened a meter lid and found 20-30 snakes in the pit. We had to call out someone to deal with the snakes before I would go in there and read the meter.”

It's a much more efficient process today.

“We once had a small army of walkers that each read 350 to 400 accounts a day," said David Kneebone, meter reading supervisor. "Now, a team of four readers each collect anywhere from 4,000 to 6,500 reads per day using a drive-by system.”

According to John Plonsky, customer service field manager, the advancement enabled Denver Water to move from bimonthly to monthly billing, providing customers with a better understanding of their water use.

“Now we want to take it a step further,” said Plonsky. “The next iteration of meter reading technology, known as Advanced Metering Infrastructure, could provide even more information to customers and increase efficiencies.”

AMI is a cellular based system that sends automatic meter reads to the cloud over a shorter time interval than what is captured monthly with the vehicles. The data can then be used for identifying water-use trends, helping to indicate possible leaks.

But, everything comes at a cost, especially when you consider there are more than 240,000 meters that would need to be upgraded. In this case, it could be to the tune of $63 million.

“Before investing in new technologies, we spend a lot of time analyzing and piloting to ensure it makes good business and financial sense for Denver Water and our ratepayers,” said Plonsky. “In this case, we’ve determined that we could benefit by phasing in a hybrid system so we’re only upgrading technology to targeted areas.”

This year, for example, Plonsky said meters around Denver International Airport — which currently take readers three days to capture because of the additional security restrictions for driving on the airfield — will be upgraded.

Additionally, hydrant meters, which are mostly used at construction sites, will also be upgraded so contractors no longer have to report their usage back to Denver Water where the customer relations team has to manually enter the data into the system. It will now automatically be collected in the cloud.

“We’ll continue to investigate other implementations for AMI and roll it out in strategic phases over the next few years,” said Plonsky. “As we do with everything, we’ll measure our success against cost, time and service when implementing new technologies and opportunities that arise in this innovative industry.”