After the fire: A wintery check on water quality

They snowshoed through a campground hidden under soft drifts, stepped carefully to the banks of the Middle Fork of the Williams Fork River, then broke the ice to find free-flowing water.

Nick Riney and Tyler Torelli worked efficiently, dipping a long-poled scoop into the waterway and filling several pint-sized plastic bottles with samples of the cold, clear stream.

Sturdy even in finger-pinching cold, the two set up a make-shift lab on the back end of the Sno-Cat, pulled equipment out of chubby metal suitcases and ran field tests right on the spot. Twenty degrees and snowfall aren’t the ideal working conditions for most, but these guys consider it a “pretty good office” all the same.

And their work on a mid-February day in Grand County gave Denver Water’s Water Quality Operations team an early look at how last summer’s Williams Fork Fire, which burned nearly 15,000 acres northeast of Silverthorne, might have affected the water flowing through the area.

See and hear what’s required to do this work:

By sampling water as it pours through the mountains, long before it reaches any reservoirs or treatment plants, Denver Water can understand what’s happening on the landscape. Samples that veer from typical readings could indicate unexpected pollution, echoes of old mining activity or, increasingly, the impacts of forest fires.

Understanding those impacts helps prepare water quality experts for potential impacts to reservoirs or treatment processes.

The field test results came back in a healthy range, with no indication yet that a significant amount of sediment left by the summer of record fires in Colorado had ended up in the water.

“That’ll change,” Riney said, as the winter turns to spring and melting snow and monsoons more readily pull soil and ash from the scorched hillsides to the east of the tributary.

“But right now, this water is clean. Turbidity is low. We like to see that,” he said. “We’ll keep tracking these spots every month and try to understand just how much damage this fire did to the landscape.”

To be sure, the burned lands around the Williams Fork River don’t present a risk to Denver’s drinking water, primarily because this water travels to an “exchange” reservoir, where it will be sent down the Colorado River to make up for other West Slope water that is diverted to the Front Range.

Even so, understanding the impacts of the fire on water quality is important, allowing Denver Water and its partners, including the U.S. Forest Service, to take steps to prepare for, and reduce, those effects.

Denver Water recently began making monthly treks to this high-country stream to monitor a wetland protection project nearby. The utility has long made quarterly trips to the area as part of its broader field-testing program to track water quality across its mountain watershed.

As part of that work, Water Quality Operations crews visit eight counties and collect samples from 77 locations. It’s work that’s distinct from the testing that goes on at reservoirs, water treatment plants and within the distribution system that bring water to household taps.

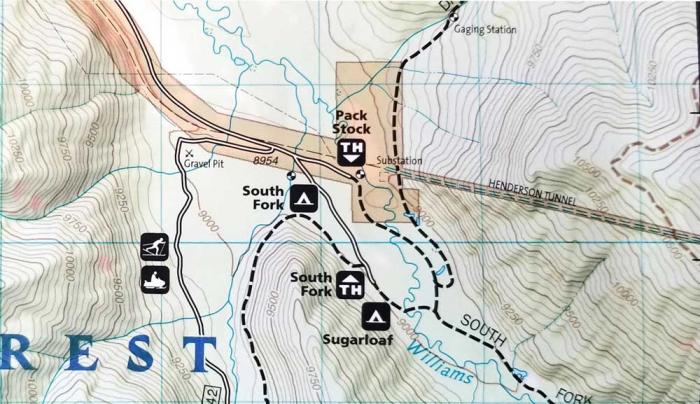

To collect samples from the Middle Fork stream, Riney and Torelli towed a Sno-Cat up and over Ute Pass Road off Highway 9, turned south in County Road 30 and went to work near Sugarloaf Campground.

“This sampling work keeps us well attuned to what’s happening in our watershed and can at times serve as an early warning for issues we may need to be watching out for further downstream,” said James Berrier, water quality monitoring supervisor at Denver Water. “We want to understand, is this just a temporary issue or something that could have a longer-term impact?”

Sampling teams measure for an array on indicators. In the field, they look at temperature, pH (which measures acidity), conductivity (which helps determine salt levels), turbidity and dissolved oxygen, which is an important factor for aquatic life.

Other water samples are transported back to Denver Water’s laboratory at the Marston Treatment Plant in southwest Denver (which will be moving in the future to its new home at Denver’s emerging National Western Center). Tests there include measuring for fluoride, chloride, nitrates, E. coli, nutrients and dissolved metal.

Samples collected a few months from now may shed light on how much damage the Williams Fork fire did to the land.

Burned Area Emergency Response teams with the U.S. Forest Service have initially concluded that the fire did varying levels of damage. Their assessments found 23% of the area suffered high-intensity burn, while 40% was unburned or experienced low-intensity fire.

Burn levels also can show up in water quality, through indicators such as ash, sediment, metals and other signatures.

“Soil erosion modelling predicts that post-fire erosion rates are generally very low (close to pre-fire conditions) in areas with minimal fire impacts on ground cover and soils. However, rates of erosion increase dramatically ... in moderate and high soil burn severity areas, especially on steeper slopes,” according to the response team’s December 2020 assessment.

Denver Water has already accumulated significant expertise and partnerships related to wildfire impacts. Collaborative efforts include From Forests to Faucets, a team approach from Denver Water, the Forest Service, the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the Colorado State Forest Service.

These agencies, together with local groups, address overgrown forests on the front end with tree-thinning projects and repairing landscapes damaged by the kind of intense fires that dramatically slow the recovery of soils and vegetation.

“We have experience, unfortunately, with the havoc that wildfires and their aftermath can wreak on our water quality,” Berrier said, referencing major fires in the late 1990s and early 2000s that put enormous strain on reservoirs and treatment on the south end of Denver Water’s collection system, challenges that the utility is still working to overcome today.

“Tracking impacts to the water once the fires are out is a key step in getting our arms around what might be in store in the years to come.”