Denver Water snowpack peaks below average

While parts of the western U.S. saw record-breaking snowfall during the 2022-23 winter, the mountain snowpack Denver Water relies on to serve its customers ended up below average.

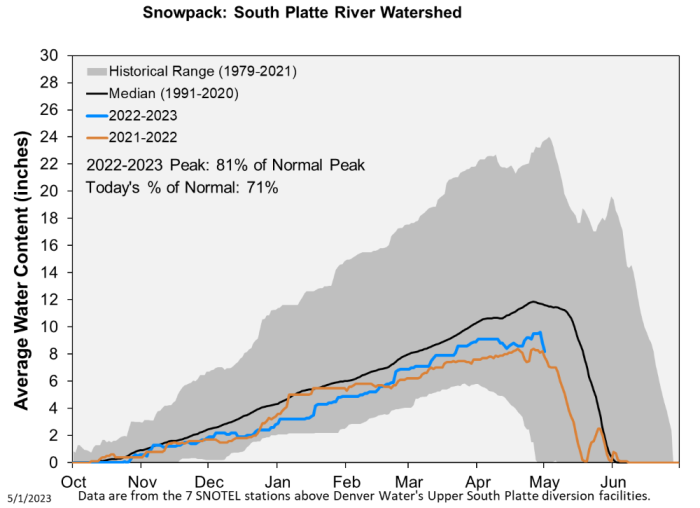

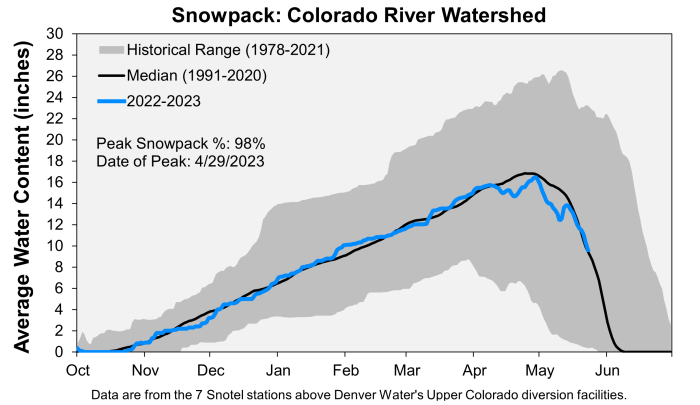

Denver Water collects half of its water from snow that falls in the Upper South Platte River Basin. The other half comes from parts of the Upper Colorado River Basin.

This year, the snowpack in the two collection areas peaked at the end of April . In the Upper South Platte, the April 26 peak was 81% of normal, while the Upper Colorado on April 29 peaked at 98% of normal. The winter's below-average result came despite the mid-May deluge that saw the mountains pick up extra inches of snow, while 4 inches of rain fell in the metro area.

“While we didn’t have the banner snow year that other parts of the West saw, the weather pattern in our collection area brought consistent snowfall with storms nearly every week this winter,” said Nathan Elder, water supply manager at Denver Water.

“The good news is that we still expect the upcoming spring runoff to be enough to fill our reservoirs this year.”

Elder said he does not anticipate additional watering restrictions beyond Denver Water’s annual summer watering rules.

Airborne Snow Observatory

Monitoring the mountain snowpack is critical to Denver Water because once the snow melts, it becomes the water supply for the 1.5 million people the utility serves in Denver and surrounding suburbs.

Traditionally, Denver Water has relied on snowpack data gathered by crews trekking to designed sites to measure snow samples, recorded by automated backcountry weather stations called SNOTELs and historical records.

In 2019, to help improve water supply forecasts, Denver Water began working with Airborne Snow Observatories Inc., or ASO for short, to gain a fuller picture of the snowpack. The company uses advanced technology developed at NASA to measure the snowpack that's built up across entire watersheds.

"Getting more and better information about the snowpack from ASO before the snow starts to melt improves the accuracy of our spring runoff and water supply forecasts for the coming year,” Elder said.

“Having the ASO information in the spring helps us manage our water resources and gives us a better idea if we’ll need to have watering restrictions for our customers in the summer. The data also gives us a very good idea of how the spring runoff in the rivers could impact the environment and recreation.”

Space age tech

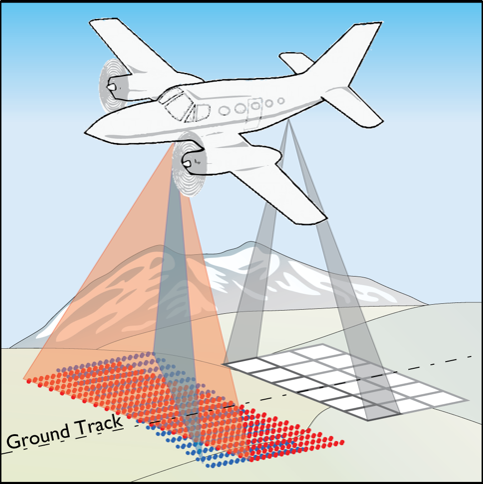

ASO planes fly with two key pieces of technology and equipment onboard: a lidar and an imaging spectrometer.

The spectrometer measures how much solar energy is reflected by the snow. This information is used to help determine how fast the snowpack will melt.

Lidar, which stands for light detection and ranging, uses beams of light to measure distance. To determine snow depth, the plane flies over a watershed in the summer and uses lidar to scan the earth’s surface when it's free of snow.

Then in the spring, when the landscape is covered with snow, the ASO team flies over the same territory again and measures the distance from the plane to the snow surface below. By comparing the differences in elevation, the ASO team is able to very accurately calculate the depth of the snow.

Digging it old school

To supplement the data collected from the plane, ASO also incorporates three “old-school” sources of data. It uses information collected by automated weather stations called SNOTELs, from snow samples collected and measured by crews at pre-determined locations in watersheds, and taken from samples collected by the ASO team or partners from snow pits dug in the same watersheds the plane flies over.

This ground-based data helps to verify the airborne snow-depth measurements. The ground data also provides snow density information, which is used to calculate the volume of water in the snowpack, called the snow water equivalent, or SWE.

“We’re able to use the traditional methods in combination with our next generation technology to measure the mountain snowpack to an accuracy that has never before been possible,” said Jeffrey Deems, ASO's co-founder.

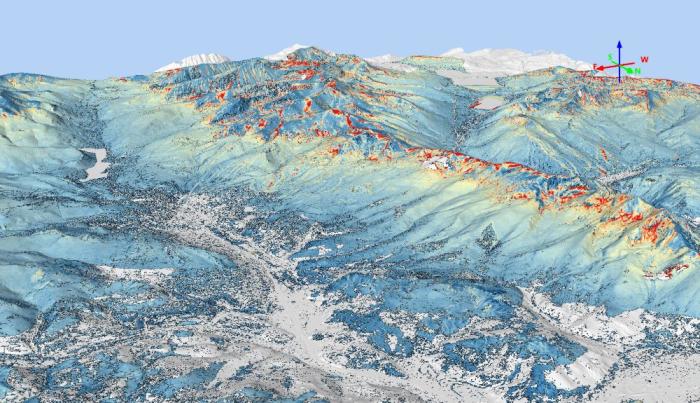

Deems said the data from the ASO flights is incredibly valuable because the plane can accurately measure the snow across an entire watershed and also at high-elevation mountain tops that are inaccessible by crews and don’t have automated weather stations.

In the first set of 2023 ASO flights conducted in April, which aimed to capture the peak snowpack, the ASO team calculated that there was 108,000 acre-feet of water packed into the snow in the Upper South Platte Basin, 175,000 acre-feet of water in the Blue River Basin which feeds into Dillon Reservoir, and 104,000 acre-feet of water in Denver Water’s Moffat collection system in the Fraser River Basin.

A second round of flights are scheduled for late May or early June to track how fast the snow is melting and to capture any new snow that may have accumulated from spring storms.

“Having ASO really helps reduce uncertainty and improve decision making for our water planning and each flight uncovers new insight into the snowpack that is otherwise unmeasurable,” Elder said. “Our first charge is to ensure we have an adequate water supply for our customers, and the sooner we can make that determination the better.”

Elder said traditional snowmelt forecasts can have significant errors or wide ranges, which makes it more challenging to manage water supplies.

Building a statewide program

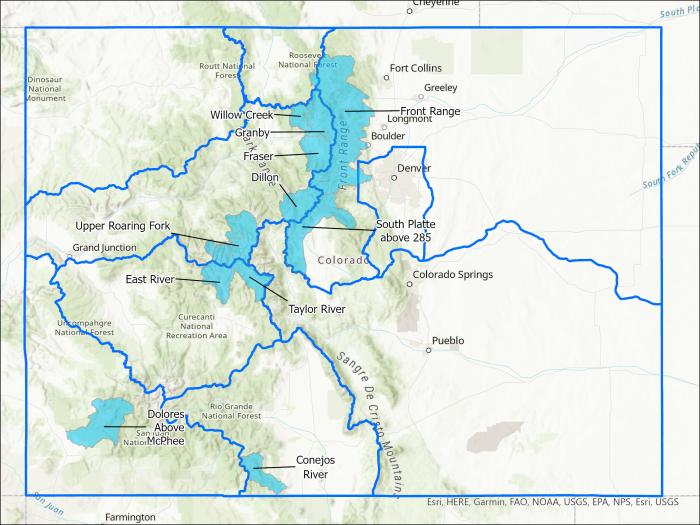

In 2023, ASO flew over eight regions in Colorado (including Denver Water’s watersheds in the Upper South Platte, Blue, Fraser, and South Boulder Creek river basins) as part of a statewide collaborative effort with the Colorado Airborne Snow Measurement program or CASM.

The CASM program includes agricultural and municipal water providers such as Denver Water, as well as environmental groups and nonprofits with support from the Colorado Water Conservation Board and federal agencies.

Recognizing the value of building a statewide ASO effort, Denver Water helped lead the coordination and facilitation of the CASM program since its inception in 2021.

"Having accurate water supply data helps all water users,” said Taylor Winchell, climate adaptation specialist at Denver Water. “Our goal with CASM is to create an annual ASO program so we can pool resources from across the state and across various water interests.”

While 2023 was the fourth year that Denver Water sponsored ASO flights in the Blue River Basin, it was the first year of ASO flights in the Upper South Platte River Basin.

The Upper South Platte flights were funded by a partnership effort that included Denver Water, Aurora Water, Chatfield Reallocation Mitigation Company, Metro Basin Roundtable and the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

Benefits today and tomorrow

Winchell said one of the big benefits of the ASO flights is that the data is available within a few days of collecting it, so water managers have a better estimate of how much water supply they’ll have for the coming year — and when to expect the water to end up in mountain streams.

The other benefit is having a wealth of high-quality data covering thousands of square miles to monitor the effects of climate change.

“As our snowpack changes with the changing climate, being better able to measure that snowpack becomes more important as more snow falls as rain, as the timing of the spring melt changes and as snow falls at ever-higher elevations because of warming,” Winchell said.

“We can’t rely as much on historical snowpack datasets to understand the new snowpack reality.”

ASO, which also conducts data collection flights in California, Wyoming, Oregon and internationally, also continues to develop its technology and modeling to help water providers get the information they need.

“We're really proud of what we’re doing,” Deems said. “We love the snow and feel like we're making a difference in helping our society better understand our mountain snowpack reservoir.”