The legacy of Colorado’s largest wildfire

Editor’s note: This story was originally posted on TAP in 2017, 15 years after the Hayman Fire, then the largest in Colorado’s history, burned 137,760 acres in the summer of 2002. But following the summer and fall of 2020, the Hayman Fire fell to fourth on the list of Colorado’s biggest fires.

Colorado’s biggest wildfires are: the Cameron Peak fire, which started Aug. 13, 2020, and burned 208,913 acres; the East Troublesome fire, which started Aug. 14, 2020, and burned 193,812 acres; and the Pine Gulch Fire, which started July 31, 2020, and burned 139,007 acres.

The ominous plume of smoke rising in the skies southwest of Denver. The ash falling on cars like large dried-up snowflakes. Many who lived in Colorado in the summer of 2002 will never forget the Hayman Fire, which burned 137,760 acres before it was over. Hayman still holds the dubious title as Colorado’s largest recorded wildfire.

This June marks the 15th anniversary of the destructive blaze, and Denver Water continues to deal with the aftermath. The fire seared through sizable portions of Denver Water’s watershed, reaching Cheesman Reservoir on its second day, where it destroyed 7,500 of the 8,500 forested acres Denver Water owns at the reservoir.

Front-row seat

Bill Newberry, one of Denver Water’s caretakers at Cheesman, got a front-row seat to the fire’s destruction. Newberry, who retired in 2014, stood near the reservoir’s shoreline as the fire blew through the area. He said the firestorm roared like a hurricane as it approached, and there was considerable heat and smoke, though he didn’t have to go into the water to escape the blaze.

Thankfully, the fire spared all of Denver Water’s caretakers, homes and buildings at Cheesman other than three small storage sheds. But what it left in its wake was a blackened landscape with only a few trees lining the reservoir, creating a danger of erosion and sedimentation problems from subsequent rains.

Traps and racks

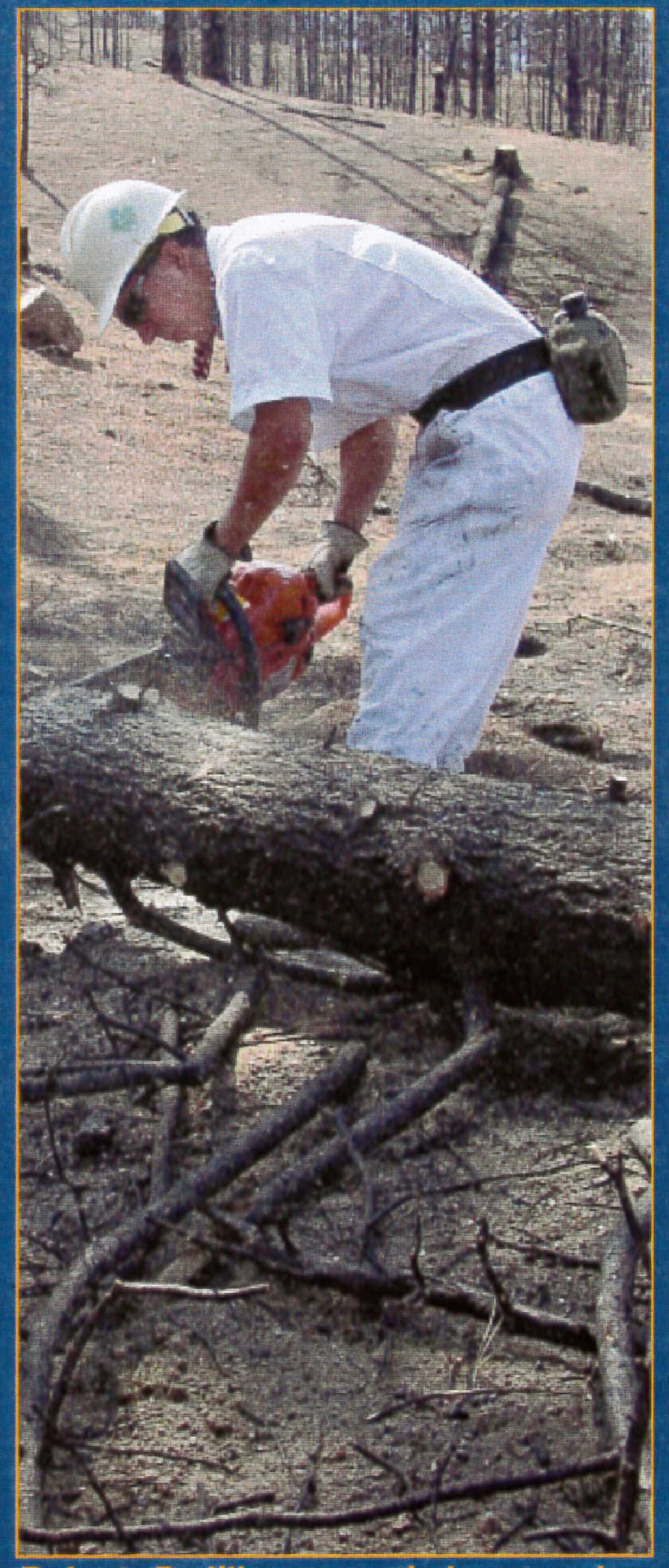

Immediately following the fire, Denver Water sent employees to help erect sediment traps made of straw bales and trash racks fashioned from downed trees. The traps and racks were positioned across drainages to catch ash and debris after heavy rains. Denver Water then built more permanent rock sediment traps to capture ash, sand and other debris from Turkey and Goose creeks, preventing that material from entering the reservoir and causing operational challenges.

The crews building the traps were used to spending their days laying new pipe in Denver’s streets, and many had never even used a chainsaw. But given the 2002 drought that had parched the city and led to severe watering restrictions, Denver Water had suspended new pipe installation. Each day, 40 to 45 workers were bused from Denver to Cheesman to help build the sediment traps.

“I was on a pipeline crew in Denver, and they moved us up there after the fire hit,” said Bobby Padilla, now a senior work planner at Denver Water. He worked at Cheesman for three years after the fire, helping with the restoration efforts. “I’ll always remember the devastation. The burnt trees looked like telephone poles with nothing on them, and everything was burnt and dark. When it rained, there were rivers everywhere — there was nothing to slow down the water.”

Fifteen years after his unusual work assignment, Padilla is still in awe at the damage of the fire. “I can’t believe how fire damages and ruins land. You could tell it was intense,” he said.

Financial flames

When Hayman tore through the watershed, Denver Water was still dealing with fire fallout from the 1996 Buffalo Creek fire, which burned 11,900 acres near Cheesman. In the aftermath of both fires, Denver Water has spent more than $27 million on water quality treatment, sediment and debris removal, reclamation techniques and infrastructure projects.

The combination of the two fires, followed by significant rainstorms, resulted in more than 1 million cubic yards of sediment accumulating in Strontia Springs Reservoir. Prior to the wildfires, the reservoir had approximately 250,000 cubic yards of sediment, which had been accumulating since 1983, when the dam was completed. Increased sediment creates operational challenges, causes water quality issues and clogs treatment plants.

Sprouts of recovery

After the fire, Denver Water spent more than 10 years working with volunteers and Colorado State Forest Service crews to plant about 25,000 trees per year on the 7,500 acres of Denver Water property destroyed by Hayman.

Following the tree-planting effort, the From Forests to Faucets partnership began in 2010 between Denver Water and the U.S. Forest Service – Rocky Mountain Region. More than 48,000 acres of National Forest System lands have been treated so far, accomplishing important fuels reduction, restoration and prevention activities.

But in many areas, the fire burned so hot it changed the chemistry of the soil in the months following the fire. Natural regeneration has been difficult, which is why Denver Water continues to work to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

After signing the renewal for the From Forests to Faucets partnership in February 2017, Denver Water CEO/Manager Jim Lochhead reiterated the need to stay vigilant. “We have a responsibility to our customers to provide safe, reliable water,” he said. “We also have an obligation to be a good steward of our natural resources. By protecting our watersheds, we’re also preserving our water.”

More photos of the Hayman Fire aftermath: