Water Year whiplash for Denver Water

Water Year 2022 started slow, lit up at wintertime, dried up in early spring, leaped back into action in late summer, then got lazy in early fall before one last hurrah.

The erratic spurts over the just-completed “water year,” the 12-month span between Oct. 1 and Sept. 30 that hydrologists use to track water trends, added up to a not-terrible-but-not-great-either result for Denver Water.

The most noticeable events included a very slow start to mountain snowfall through the first three months (bad), a second straight year of healthy summer monsoons in the mountains (good) and a sizable split between the water fortunes of Denver Water’s collection area (the high country and foothills) versus its service area (Denver and parts of five surrounding counties).

In short, it translated into a reasonably good water year in higher elevations and a far drier one for the 1.5 million people the utility serves in Denver and nearby suburbs.

One memorable result? Denver’s first snowfall came Dec. 10 — the latest first snow on record for Denver.

“Every water year is different, and Mother Nature throws new challenges at us almost every time,” said Nathan Elder, Denver Water’s manager of water supply. “But timely rains and good customer practices helped us keep reservoir levels in solid shape and we soldiered through an up-and-down year.”

Stay up to date with what’s on TAP. Sign up for the free weekly email.

The very best news appears to be the way a second consecutive year of strong monsoon rains and higher humidity replenished dry soils in the mountains.

Should Colorado enjoy a deeper winter snowpack this year, it would mean more melting snow in the spring could find its way to streams and reservoirs in 2023, rather than vanishing into parched soils as has been the case in recent cycles.

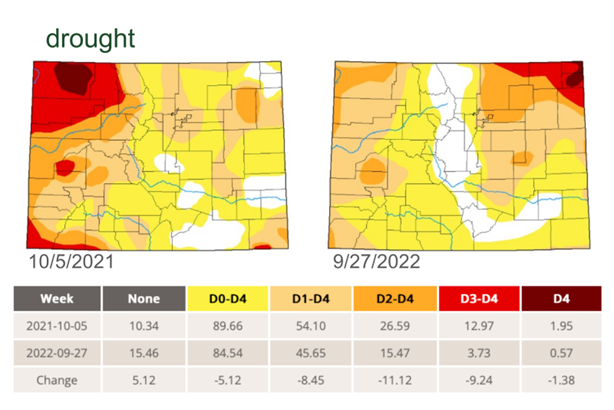

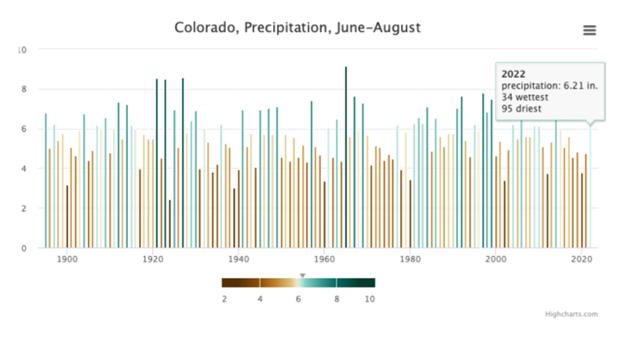

Dice up the numbers in a different way and zoom out from Denver Water and the picture looked better from a statewide perspective, with summer precipitation levels the best since 2015.

Additionally, soil moisture is at its highest levels in three years, according to climate trackers at Colorado State University and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service via recent reporting from Marianne Goodland in the Denver Gazette.

While those are positive developments, experts across various agencies agree that Colorado and its water utilities need a string of strong winters, and preferably some wetter/cooler years overall if we’re ever to see longer-term improvements in hydrology.

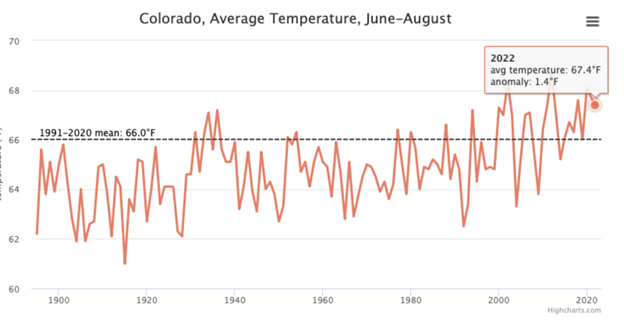

But in an era of steady climate change that appears to be unlikely. Colorado’s summer of 2022 was the sixth warmest in the 128-year record maintained by state climatologists.

Denver Water’s supply managers faced some tough conditions in the 2022 water year.

Ongoing work to expand capacity at Gross Reservoir has limited storage in the facility west of Boulder. At the same time, unusually dry conditions on the South Platte River downstream of Denver left farmers calling on water rights dating all the way back to 1871 (just a decade shy of the oldest water rights on the river).

These rights are senior to all of Denver Water’s South Platte River reservoirs and made it difficult to fill those reservoirs. Cheesman Reservoir’s 1889 right is the most senior storage right in Denver Water’s portfolio.

All of that meant more water bypassed Denver Water’s reservoirs to meet those agricultural calls and there was less ability to make up that water by pulling from Gross Reservoir on the north side of the utility’s system. It also meant higher-than-average flows through the Roberts Tunnel to help supplement South Platte supplies.

But, in a hat tip to customers and Mother Nature, smart irrigation techniques (like turning off systems in rainy periods) and solid summer precipitation in the higher country (and, at times, in metro Denver) helped keep Denver Water’s reservoirs at just below average levels.

In fact, all that combined to close a storage gap. Reservoirs were 5% below average in July. But by the end of September that deficit fell to just 1% below average.

And there was more good news. Another good summer of monsoons kept wildfires at bay, which was a big relief after the devastating water year of 2020, when record-setting late-season fires extended the burn season into October.

On the other side of the ledger, another hot September continued a troubling trend.

See how Denver Water measures the snowpack — from 20,000 feet.

The last month of summer keeps getting warmer. This one set a new record for 90-degree days (10), which — along with other factors — make it the fastest-warming month in the Denver area when compared to the previous 30-year block of records that spans 1981 to 2010.

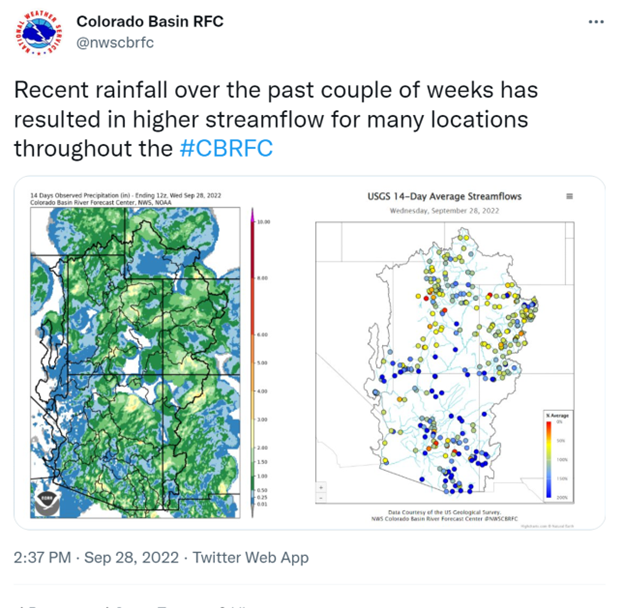

Conditions improved in late September, when late-season moisture boosted streamflows and dampened soils, especially in the high country, bringing a happy ending to the water year.

Some broader context also is in order.

The 2022 Water Year for the wider Colorado River Basin was another poor one. One simple metric captures the status of the basin: The amount of water in the two major reservoirs on the river dropped dramatically, with Lake Mead falling 1.8 million acre-feet from a year ago and Lake Powell falling 1.5 million acre-feet in the same time frame.

Trends in the Colorado River Basin matter a great deal to Denver Water, as the utility gets about 50% of its supplies from the headwaters of the basin.

The new 2023 Water Year that began Oct. 1 is off to a good start for Denver Water.

After the nip-and-tuck of the summer months, the utility’s reservoir levels have hit their average mark heading into late fall and winter, just where water managers want to be at the beginning of the snow-accumulation season.

“We hope Mother Nature makes a New Water Year Resolution to provide ample snow and rain fall in the water year of 2023,” said Elder.

It’s he and his team who must now begin planning for the various scenarios winter and spring might bring.

You, too, can make a resolution for the New Water Year: to reduce your water use. Check out Denver Water’s website for rebates and ways to use water efficiently.